May 23, 2019- September 02, 2019

This summer, Neue Galerie New York is pleased to present George Grosz’s monumental 1926 canvas Eclipse of the Sun, which is on special loan from the Heckscher Museum of Art in Huntington, New York. The painting is the centerpiece of “Eclipse of the Sun: Art of the Weimar Republic,” a focused exhibition that includes additional paintings and drawings by Grosz, along with a selection of art by Otto Dix, Max Beckmann, Otto Griebel, Christian Schad, Rudolf Schlichter, and Georg Scholz. Many of the works are drawn from the extended collections of the Neue Galerie, and together demonstrate the artistic output that coincided with a moment of extreme political unrest in Germany.

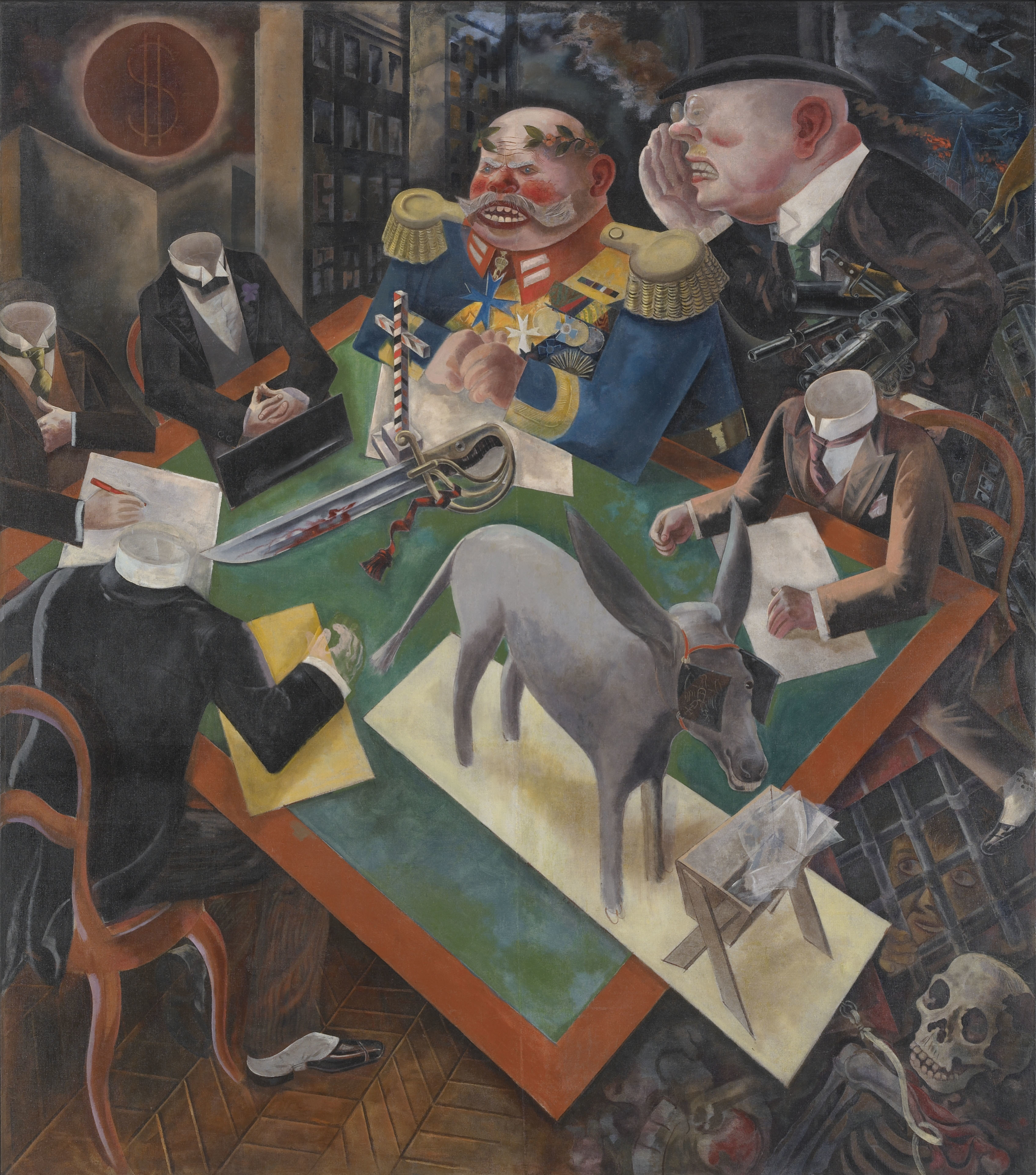

George Grosz (1893-1959)

Eclipse of the Sun, 1926

Oil on canvas

The Heckscher Museum of Art, Huntington, N.Y.

© 2019 Estate of George Grosz / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

In Eclipse of the Sun, Grosz vividly captures the rampant political and social corruption that characterized Germany in the mid-1920s. Set against the backdrop of a city in flames, the central figure depicted is Paul von Hindenburg, the nearly-eighty-year-old president of Germany at the time this was painted, and easily recognizable for his walrus moustache. He proudly wears his military uniform, bedecked with medals and with a laurel leaf crown perched atop his bald head. Hindenburg’s portly physique is in sharp contrast to the group of slim and headless financiers in formal attire who join him around the table. They bask in the glow of a darkened sun illuminated with a dollar sign—an acknowledgment of America’s investment in Germany post-World War I. A corpulent “man of industry,” wearing a top hat and toting weapons and a miniature train under his arm, whispers discreetly in Hindenburg’s ear. But Hindenburg has focused his attention elsewhere—toward a spot just beyond the bloodied sword and funerary cross resting directly in front of him on the table. Rather bizarrely, a donkey wearing blinders decorated with the German eagle is balanced on a board tethered to a skeleton. The other participant in this motley group is a more somberly dressed but also headless man whose foot rests precariously on the prison bars below. Eclipse of the Sun was one of Grosz’s “favorite pictures” and it offers a microcosm of the Weimar Republic, alluding to the competing interests that struggled to control the fledgling democracy.

Grosz and his peers portray the cacophony of the metropolis and the unrest that characterized the birth of the Weimar Republic. It was a period of tremendous political and social tumult and marked by a burst of creative energy in Germany. In the aftermath of World War I, many artists moved away from an Expressionist approach in favor of one marked by a more harsh and objective depiction of the world around them. This became known as the Neue Sachlichkeit or New Objectivity movement.

Grosz, in particular, used his vision to shine a spotlight on the rampant political corruption that marked this short-lived period of democratic governance. His scathing critique of the regime—he was a member of the Communist Party—made his life more difficult, and he ultimately chose emigration in order to ensure greater artistic freedom. Grosz came to the United States in 1932 and taught at the Art Students League of New York. In January 1933, he emigrated to America and became a naturalized citizen in 1938. He remained in the United States until 1959, when he returned to Berlin and died shortly thereafter.

ADDITIONAL WORKS ON VIEW

Grosz’s masterwork will be complemented by additional paintings and works on paper by the artist. Max Beckmann, Otto Dix, Otto Griebel, Christian Schad, Rudolf Schlichter, and Georg Scholz will also be represented in the show.

Standout works include Grosz’s 1919 Panorama (Down with Liebknecht), a nightmarish rendering of the bloody Spartacist uprising in Germany early in 1919, which led to the political murder of leaders of the German Communist Party, Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg. The traces of red that wash over the image are linked both to the violent execution of Liebknecht, Luxemburg, and so many others, as well as to the hedonistic atmosphere that was a hallmark of Berlin in the 1920s.

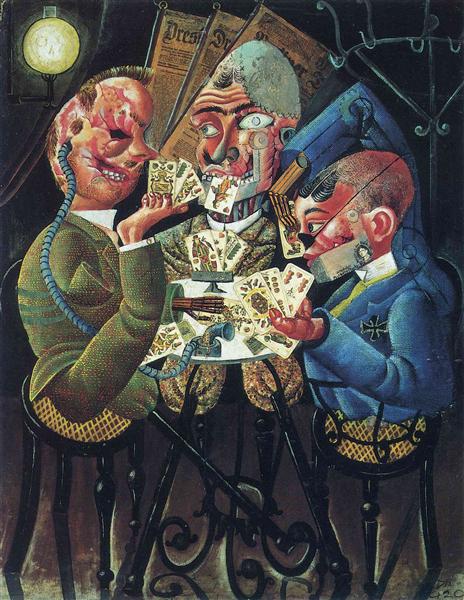

Likewise Dix’s 1920 study for

the painting The Skat Players is a searing indictment of modern warfare. Based upon a scene Dix observed, it depicts three grotesquely crippled war veterans engrossed in the card game skat. The artist’s gaze is unflinching. He does not romanticize their battle scars nor does he seem to pity them either.

![zoom Max Beckmann. The Way Home (plate 2) [Der Nachhauseweg (Blatt 2)] from Hell (Die Hölle). (1919)](https://www.moma.org/s/ge/collection_images/resized/183/w500h420/CRI_169183.jpg)

The Way Home (plate 2) [Der Nachhauseweg (Blatt 2)] from Hell (Die Hölle)

- Date:

- (1919)

- Medium:

- One from a portfolio of eleven lithographs (including front cover)

![zoom Max Beckmann. The Ideologists (plate 6) [Die Ideologen (Blatt 6)] from Hell (Die Hölle). (1919)](https://www.moma.org/s/ge/collection_images/resized/124/w500h420/CRI_169124.jpg)

The Ideologists (plate 6) [Die Ideologen (Blatt 6)] from Hell (Die Hölle)

- Date:

- (1919)

- Medium:

- One from a portfolio of eleven lithographs (including front cover)

The period of unrest that marked the birth of the Republic was followed by a brief period of economic prosperity. This gave rise to the emergence of the so-called “New Woman,” physically notable for her short hair, sexual liberation, and desire for self-determination. Artists were fascinated by this figure and how she coped with her newfound freedom. Dix, for instance, often trained his eye on women who struggled to find their place in a merciless world, many of whom fell into prostitution in a desperate attempt to support themselves. By contrast, the liberated women of Schad and Schlichter appear almost lifeless, as if they had become automatons, suggesting that the price of freedom came at the considerable cost of their souls.

For instance, Schad’s 1928 Two Girls portrays pleasure without passion, except perhaps for the voyeuristic observer.