Matisse Picasso, an examination of the lifelong relationship between Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso, two of the most influential artists of the twentieth century, opened at MoMA QNS, its only U.S. venue, on February 13, 2003. It remained on view through May 19, 2003.

The exhibition traced the artistic dialogue between the two men over the course of a nearly half-century relationship that was much closer, visually and psychologically, than has previously been acknowledged. Matisse Picasso featured 133 works in groupings that reveal the affinities and influences, as well as the contrasts, between the artists.

The exhibition began in 1906, with self-portraits painted by the artists at the time of their meeting in Paris and with works they exchanged soon after. It ended in 1961, with sculpture by Picasso that paid tribute to Matisse, who died in 1954.

The exhibition was a collaboration between The Museum of Modern Art, New York; Tate Modern, London; and the Réunion des musées nationaux/Musée Picasso, Musée national d’art moderne/Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, and was shown at Tate Modern in London from May 11 to August 18, 2002, and at the Galeries nationales du Grand Palais in Paris from September 22, 2002 to January 6, 2003. Eight paintings were unique to the MoMA exhibition, enabling the curators to assemble fresh juxtapositions not seen in the previous showings.

Historians have often set the two painters in opposition, presenting Matisse as a maker of luxuriously colored, harmonious images, while Picasso is seen as the more conceptual painter, emphasizing form over color and anguish over serenity. This exhibition demonstrates that even as the painters worked in open rivalry, observing each other’s moves and competing for critical attention in the art world, they were, in Matisse’s words, “strangely in agreement.” Picasso echoed the sentiment when he stated, “No one has looked at Matisse’s painting more carefully than I, and no one has looked at mine more carefully than he.”

The exhibition was comprised of 83 paintings (including cut-outs), augmented by 24 sculptures, in painted sheet metal, bronze and plaster, and 26 works on paper; including drawings and cut-paper collage. The open architecture of MoMA QNS provided for optimum flexibility in exhibition design, enabling MoMA to create a customized installation of these works. The largest part of the exhibition concentrated on works produced between 1906 and 1917, when the painters were in open competition.

Even at this early stage, they were exploring remarkably similar thematic territory, as seen in the juxtaposition of

Picasso’s Boy Leading a Horse (1906)

with Matisse’s Le luxe I (1907),

which both avoid clear narrative in favor of quasi-mythic subject matter.

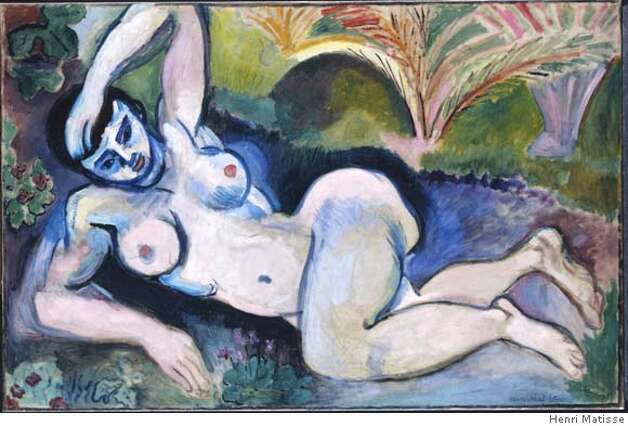

Both Matisse’s celebrated and controversial Blue Nude: Memory of Biskra (1907)

and Picasso’s Bather (1908-09)

retain clichéd poses of seductive self-display, even as they challenge the canons of art and feminine allure.

In Picasso’s seminal painting Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907)

and Matisse’s Bathers with a Turtle (1908),

an important pairing shown only at MoMA, contrast between the two artists emerges.

In Bathers, Matisse rejects Picasso’s fractured tribal primitivism—which he found uncouth and shocking—in favor of a different “primitive” model recalling such early Renaissance painters as Giotto. Despite their differences, both Demoiselles and Bathers defy the long-held rule that large-scale figural compositions require a clear narrative.

From 1909 until the end of World War I, Cubism dominated the dialogue between Matisse and Picasso, as demonstrated in a superlative grouping of eight paintings of women. These works integrate naturalistic curves with the sharp geometry of Cubism and show the influence of African art, as seen in the masklike elements and severe, abstracted lines in

Matisse’s 1913 portrait of his wife

and in Picasso’s Woman in Yellow (1907).

In Portrait of Mlle Yvonne Landsberg (1914), Matisse employs radiating arcs to surround the figure, while in Portrait of a Young Girl (1914) Picasso pushes cubistic fragmentation of the figure much further, coupled with a bravura display of pattern and color reminiscent of Matisse.

Matisse’s attention to the forms and pictorial strategies of Cubism could also be seen in the juxtaposition of two major paintings:

Matisse’s Goldfish and Palette of late 1914

and Picasso’s Harlequin of late 1915.

In Goldfish and Palette, Matisse borrowed the large, flat shapes that Picasso had employed in his earlier experiments with papier collé (cut and glued paper collage) and incorporated them into a bigger, bolder, and more geometric composition. In turn, Harlequin echoes the strong vertical parallels and depiction of an artist’s palette seen in Goldfish and Palette, and marks a change from Picasso’s playfully ornate style of Cubism into one that was more austere. Matisse greatly admired Picasso’s painting when it was exhibited in 1915 and speculated that it was “his goldfish” that led Picasso to the breakthrough of Harlequin.

A quartet of grand-scale compositions illuminates the point and counterpoint of influence. Matisse’s elegiac memory of North Africa,

The Moroccans (1915–16),

and radical abstraction of a genre scene in The Piano Lesson (1916)

apply the principles of Picasso’s collages to paintings of heroic ambition and importance, and represent Matisse’s most dramatic response to Cubism.

During the same period, Picasso expanded on the harlequin theme and produced

Man Leaning on a Table (1915–16), his largest painting since Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, and one of the paintings that was unique to the New York exhibition.

He later responded to Matisse’s interpretation of Cubism with a playful update of his style, as seen in

Three Musicians (1921).

Beginning in 1917, Matisse moved to Nice and reverted to a more intimate, introspective, and naturalistic manner. Picasso stayed mostly in Paris and worked in diverse styles while becoming more deeply involved in Surrealism. The Surrealist ethos, which Picasso did so much to foster, served to further distance the two artists, yet they continued to study one another’s work and respond to each other in new ways.

During his early years in Nice, Matisse often used the traditional motif of the odalisque, or harem-girl. In

Decorative Figure on an Ornamental Background (1925–26),

which caused a critical uproar when it was first exhibited in Paris in 1926, Matisse positions an illogically sculpted, three-dimensional nude figure against a flamboyantly colored and patterned flat background.

Picasso could not have missed the painting or the controversy, and he responded in 1927 by painting such “anti-odalisques,” as

Woman in an Armchair (1927),

which shows a monstrous, primeval figure painted in stark and ominous colors, in keeping with the dark, Surrealist mood that informed his painting at this time.

The distorted nudes painted by Picasso from 1925 to 1930 look like brutal challenges to Matisse’s sensuous figures. In the early 1930s, however, the harshness seen in Picasso’s depiction of the female form softened after he found love with Marie-Thérèse Walter.

Picasso’s Nude in a Black Armchair (1932) could be described as “Matissean” in its color, light, pattern, plump flesh, and erotic ambience. Picasso had never before adopted Matisse’s manner so thoroughly, prompting

Matisse’s return to easel painting after years of working on a mural commission to create the bold, stately composition

Large Reclining Nude (The Pink Nude) (1935).

During World War II, while Matisse was isolated in Nice and Picasso remained in difficult circumstances in occupied Paris, they managed to exchange works and drew support from one another. After the war ended, Picasso joined Matisse in the south of France, and the now famous and wealthy artists saw each other regularly as their relationship entered its final and closest phase.

Matisse’s Large Red Interior (1948),

a dazzling depiction of his studio, represents his final expression of the vibrant relationship between line and color, and forms the summation of his career as an easel painter. It was paired with a studio interior by Picasso,

The Studio at La Californie (1955), a poignant, virtually monochrome painting produced a year after Matisse’s death in November 1954, that can justifiably be regarded as an homage to his departed friend.

When Matisse’s health began to decline in his final years, he developed a technique that allowed him to work while seated, cutting shapes from colored paper and directing assistants to form compositions. Picasso followed this evolution closely, and between 1961 and 1962 he produced bent-metal sculptures with striking affinities to Matisse’s cut-outs. A dramatic section of the exhibition showing acrobatic dancers and nudes reveals the remarkable crossovers between Picasso’s late sculptures, which became increasingly flat and pictorial, and Matisse’s cut-out paper collages, monolithic figures on flat grounds that seem to aspire to sculpture.

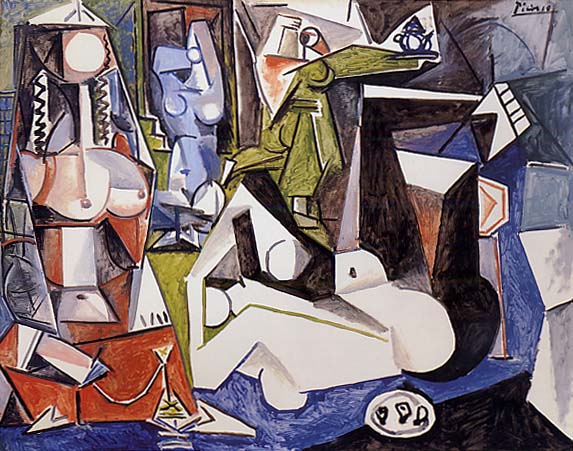

Two months after Matisse’s death, Picasso began a 15-painting cycle of variations on

Eugène Delacroix’s Women of Algiers (1834), a painting depicting odalisques in a harem—one of Matisse’s favorite subjects—and a work that both Picasso and Matisse had admired.

In one version, Women of Algiers, after Delacroix (Canvas N) (1955),

Picasso keeps both Delacroix and Matisse alive but contorts the figures in harsh, aggressive ways that are strictly his own.

The haunting final juxtaposition in the exhibition consists of two self-portrayals made at a time of personal crisis for each artist: Matisse’s Violinist at the Window (1918) and Picasso’s The Shadow (1953). In viewing them together, one can see echoes of motif, emotion, and form.

In Violinist at the Window, Matisse fuses three themes that recurred throughout his career: the window, the back view, and music. This poignant painting of lonely isolation and the consolations of art, created soon after Matisse moved to Nice during a time of transition and uncertainty, was never shown while he was alive.

The Shadow was painted when Picasso was 73, shortly after his young wife Françoise Gilot had left him. In this haunting image, a plane of afternoon light casts the artist's own shadow into their bedroom, but that shadow misses contact with the arching female form that embodies his imagination of lost love.

PUBLICATIONS:

The exhibition was accompanied by a scholarly catalogue discussing the comparisons in depth and giving relevant background information regarding the dialogue between these two remarkable artists. The clothbound catalogue contains 34 essays, each by a member of the exhibition's curatorial team.

Looking at Matisse and Picasso, published by MoMA’s Department of Education in conjunction with the New York showing of Matisse Picasso, is an accessible introduction to the ideas embedded in the exhibition, and was designed for general audiences aged nine to ninety. The 72-page paperbound volume is authored by María del Carmen González and Susanna Harwood Rubin, who are both artists and educators in the Department of Education.