Wednesday, February 13, 2013

Picturing Old New England: Image and Memory

"Picturing Old New England: Image and Memory," an exhibition that explores images of the New England past, was on view at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Smithsonian Institution. The exhibition featured 173 paintings, sculptures, prints, photographs and illustrated books made from 1865 to 1945 and major works by such artists as Winslow Homer, Childe Hassam, John Singer Sargent, Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Maurice Prendergast, George Bellows, Marsden Hartley, Edward Hopper, Maxfield Parrish and Norman Rockwell.

This exhibition grouped masterworks and popular culture images from numerous museums and private collections to explore for the first time the ways New England was treated in American art during this important period, and how New England subjects addressed the broader cultural currents in the country. The product of several years' research by Smithsonian American Art Museum senior curator William Truettner and University of Virginia professor Roger Stein, "Picturing Old New England" looked at how New England came to embody timeless American ideals—the "founders' values"—in a period of rapid and disquieting social change.

"Picturing Old New England" was arranged thematically in six sections, each built around artists with shared stylistic goals: "Constructing the Rural Past," "Gilded Age Pilgrims," "The Discreet Charm of the Colonial," "Small-Town America," "Perils of the Sea" and "Yankee Modernism." In total the featured works reveal how the idea of a never-changing New England solidified in the public imagination.

The exhibition showed that scenes of a pastoral New England were much loved by artists and their audiences. Eastman Johnson focused on an innocent, rural New England evoking earlier days.

In "The Old Stage Coach" (1871), children clamor over a dilapidated wheel-less wreck with "Mayflower" inscribed over its door, now marooned in a verdant field. Other artists like Winslow Homer and George Inness turned to such rugged wilderness areas as the White Mountains of New Hampshire and the rocky coast, creating works that celebrated the region's unspoiled beauty and grandeur.

Simultaneously, New England was born anew as the birthplace of the nation's democratic values. Howard Pyle's dramatic re-creations of scenes from the American Revolution, Augustus Saint-Gaudens's bronze sculpture

"The Puritan (Deacon Samuel Chapin)" (1887), and

"Concord Minute Man of 1775" (1889), a bronze sculpture by Daniel Chester French, provided a vivid connection to America's historic pursuit of liberty and equality.

In the 1870s a "new" New England emerged that was shaped by cities, factories, and a diverse ethnic population fed by increased immigration. However, in the imagination of Americans undergoing immense political and social change, New England became a touchstone for the past, a spiritual homeland bypassed by progress. Farm and village scenes, family portraiture and historical subjects offered audiences a reassuring look backward and reaffirmation of the founders' values. Printmakers and photographers carried the same themes into the broader currency of popular culture.

Formal portraits of Boston's "Gilded Age Pilgrims" by John Singer Sargent and Frank Benson recalled the colonial portraits by John Singleton Copley that still hung in Beacon Hill drawing rooms.

Sargent's "Mrs. William C. Endicott" (1901) presents a figure of patrician elegance, while

Benson's "Portrait of Thomas Wentworth Higginson" (1823–1911) is a more sober study of this distinguished minister, reformer, and writer.

By the turn of the twentieth century, American impressionists commonly summered in New England artists' communities, both inland and on the coast. Works like

Childe Hassam's "Church at Old Lyme, Connecticut" (1906) and

Willard Leroy Metcalf's "Gloucester Harbor" (1895) portrayed the pasts of small New England towns in softly brushed color that distanced them from the early 1900s.

In the early 1920s, Edward Hopper, John Marin, Marsden Hartley, Stuart Davis, and Yasuo Kuniyoshi returned to subjects painted by American artists some eighty years earlier.

Marin's "Pertaining to Stonington Harbor, Maine, # 1" (1926) uses a cubist vocabulary to suggest the serene days of pre-industrial seafaring commerce. Davis's views of Gloucester juxtapose modern gas pumps and traditional fishing schooners in the old fishing port.

With their focus on everyday rural life, Norman Rockwell, Maxfield Parrish and Grandma Moses portrayed yet another old New England in the 1930s. Rockwell turned New England and its citizens into archetypes for small-town America.

Norman Rockwell's "Freedom of Speech" (1943) idealizes the tradition of the New England town meeting.

Parrish's "June Skies (A Perfect Day)" (1940) is emblematic of his views of the countryside, while Grandma Moses' "In the Green Mountains" (1946) issues an invitation to a homespun and simple world. Depression-era photographs, like the anonymous "Strawberry Picker, Falmouth, Massachusetts" (ca. 1930), tell a different story. In the foreground workers bend over endless rows of fruit that reach the horizon, capturing the hardship endured by the regional workforce during this period.

More images from exhibition:

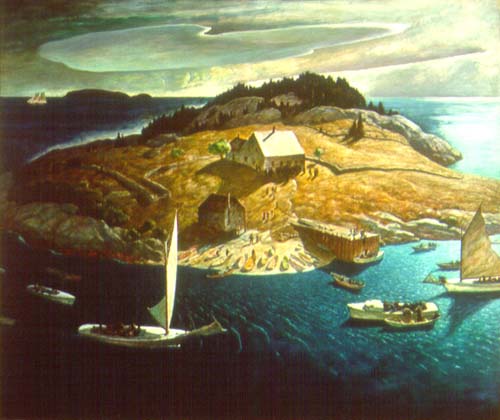

N. C. Wyeth "The Island Funeral" (1939)

Rockwell Kent, Maine Cost

Catalogue

"Picturing Old New England: Image and Memory," was accompanied by a two- hundred-page catalogue published by Yale University Press with a preface by Smithsonian American Art Museum director Elizabeth Broun, an introduction by Dona Brown and Stephen Nissenbaum, and six chapters by Smithsonian American Art Museum senior curator William H. Truettner, Roger B. Stein, Thomas Andrew Denenberg and Bruce Robertson. Biographies written by Denenberg and Judith K. Maxwell of the 115 artists featured in the exhibition are also included.