Note: This is the same exhibition held at the Tate and covered here with many beautiful images that won't be repeated here.

Combining rebellion, scientific precision, beauty, and imagination, the Pre-Raphaelites created art that shocked 19th-century Britain. On view from February 17 through May 19, 2013, at the National Gallery of Art, Washington—the sole U.S. venue—Pre-Raphaelites: Victorian Art and Design, 1848–1900 is the first major survey of the art of the Pre-Raphaelites to be shown in the United States. The exhibition features some 130 paintings, sculptures, photography, works on paper, and decorative art objects that reflect the ideals of Britain's first modern art movement.

"The Pre-Raphaelites rejected the rigid rules for painting that prevailed at the dawn of the Victorian era to launch Britain's first avant-garde movement," said Earl A. Powell III, director, National Gallery of Art. "We are thrilled to present this rare exhibition to our audiences and grateful to lenders, both public and private, as well as our generous sponsors. Notably, we have received a generous amount of loans from Tate Britain and the Birmingham Museums Trust in the United Kingdom."

The Pre-Raphaelites

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB) was founded in London in September 1848 at a turbulent time of political and social change. Many Victorians felt that beauty and spirituality had been lost amid industrialization.

The leading members of the PRB were the painters John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti and William Holman Hunt, young students at the Royal Academy of Arts. They all believed that art had become decadent, and rejected their teachers' belief that the Italian artist Raphael (1483–1520) represented the pinnacle of aesthetic achievement. Instead, they looked to medieval and early Renaissance art for inspiration. Whether painting subjects from Shakespeare or the Bible, landscapes of the Alps, or the view from a back window, the Pre-Raphaelites brought a new sincerity and intensity to British art.

Exhibition Highlights

The exhibition is organized into eight themes:

Beginnings: The Pre-Raphaelites were both historical and modern in their approach. While they borrowed from the art of previous centuries, they also listened to critic John Ruskin's call to observe nature and represent its forms faithfully. In balancing the past with the world they saw before them, the Pre-Raphaelites crafted a modern aesthetic. Some of their important early works—such as

Hunt's Valentine rescuing Sylvia from Proteus—Two Gentlemen of Verona (Act V, Scene iv) (1850–1851)

and Millais's Christ in the House of His Parents (The Carpenter's Shop) (1849–1850)

—reveal the emergence of this new style.

History: Dramatic narratives from the Bible, classical mythology, literature, or world history had dominated European art since the establishment of art academies in the 17th century. The Pre-Raphaelites rejected these grand narratives to focus on intimate human relationships. Millais set the standard, adopting a precise style and drawing from British history and popular operas while emphasizing accuracy of dress and settings. The results—seen in

A Huguenot, on Saint Bartholomew's Day, Refusing to Shield Himself from Danger by Wearing the Roman Catholic Badge (1851–1852)

and The Order of Release, 1746 (1852–1853)

—defied convention, provoked critics, and entranced audiences.

Literature and Medievalism: Pre-Raphaelitism was also a literary movement. The artists took subjects from Shakespeare, Dante Alighieri, and other medieval tales, as in Millais's beloved painting Ophelia (1851–1852). Several wrote poetry, including Rossetti, who with Elizabeth Siddall (who served as Rossetti's muse, model, lover, and eventually wife) created intensely colored, intricate watercolors based on medieval manuscript illumination and themes of chivalric love, seen in his

The Wedding of Saint George and the Princess Sabra (1857).

Soon Rossetti's younger followers Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris incorporated medieval subjects in their designs for furniture, stained glass, and other decorative arts.

Salvation: The Pre-Raphaelites addressed morality and salvation in subjects drawn from both religion and modern life. Religious and moral thinking permeated everyday life, whether in regard to ideas of class and society, relationships between the sexes, or ideals of domesticity, which they examined in works such as

Hunt's The Awakening Conscience (1853–1854)

and Ford Madox Brown's Work (1863).

Rejecting traditional religious imagery, the Pre-Raphaelites painted biblical scenes with unprecedented realism. Hunt was so committed to truthful representation that he traveled to the Holy Land, where he painted the actual settings of biblical events, seen in

The Shadow of Death (1870–1873).

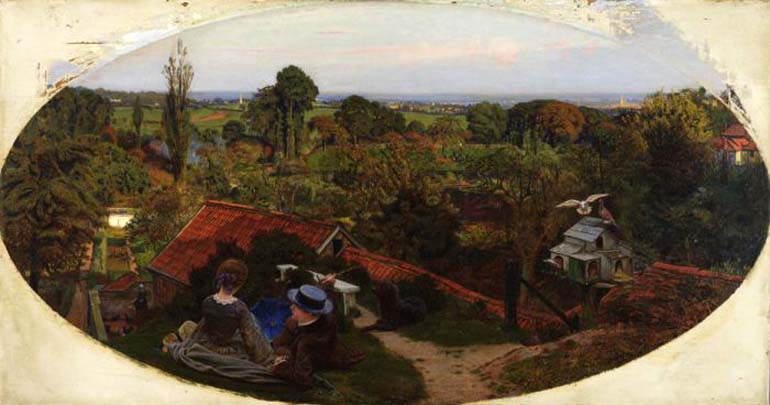

Nature: The Pre-Raphaelite artists developed a fresh and precise method of transcribing the natural world in oil paint, based on direct, up-close observation and working out of doors. At a time of debates about evolution and the history of the earth (Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species was published in 1859), Pre-Raphaelite landscape paintings reflected the artists' interest in the natural sciences, geology, botany, meteorology, and even astronomy. Groundbreaking works such as

Brown's An English Autumn Afternoon, Hampstead—Scenery in 1853 (1852–1855)

and "The Pretty Baa-Lambs" (1851–1859) newly emphasized rendering precise detail and natural light.

Beauty: Around 1860, the Pre-Raphaelites turned away from realist depictions of history, literature, modern society, religious themes, and nature scenes to explore the purely aesthetic possibilities of painting. The female face and body became the most important subjects, in erotically charged works that had little precedent. Beauty came to be valued more highly than truth, as Pre-Raphaelitism slowly shifted into the Aesthetic Movement. Rossetti was the dominant force as his work became more sensuous in style and subject, seen in

Bocca Baciata (1859), Beata Beatrix (c. 1864–1870), and Lady Lilith (1866–1868, altered 1872–1873).

Paradise–Decorative Arts: Inspired by the Pre-Raphaelites and the medieval past, Morris established a decorative arts firm in 1861 with partners Rossetti, Brown, and Burne-Jones. In 1875 Morris reorganized the company under his sole direction as Morris & Co. aiming to erase the distinction between the fine and applied arts. The firm produced tiles, furniture, embroidery, stained glass, printed and woven textiles, carpets, and tapestries for both ecclesiastical and domestic interiors. Several examples are on view, from stained glass, furniture painted with medievalized themes, and a three-fold screen with embroidered panels of heroic women on loan from Castle Howard, to popular tile, textile, and wallpaper designs, including the iconic Strawberry Thief (1883). In the last decade of his life, Morris founded the Kelmscott Press for the production of high-quality, hand-printed books. This room also includes two stunning tapestries designed by Burne-Jones and Morris from the series based on the Arthurian story of the Holy Grail.

Mythologies: Late Pre-Raphaelite paintings reflect a fascination with the world of myth and legend. Rossetti and Burne-Jones embraced imagination and symbolism, focusing on the human figure frozen in a drama. Both found inspiration in Renaissance art after Raphael, concentrating on sensuous Venetian color and the sculptural forms of Michelangelo, seen in

Rossetti's La Pia (1868–1881) and Burne-Jones' Perseus series (1885–1888). Hunt adhered more closely to the initial realist Pre-Raphaelite style, which he brought to his late masterpiece, The Lady of Shalott (c.1888–1905).

Curators and Exhibition Catalogue

Diane Waggoner, associate curator of photographs, National Gallery of Art, is the curator of the exhibition. The exhibition at Tate Britain was curated by Alison Smith, Lead Curator, Nineteenth-Century British Art at Tate; Tim Barringer, Paul Mellon Professor of the History of Art at Yale University; and Jason Rosenfeld, Distinguished Chair and Professor of Art History at Marymount Manhattan College, New York.