The Museum of Modern Art presented Pioneering Modern Painting: Cézanne and Pissarro 1865–1885, from June 26 to September 12, 2005. It was the first exhibition to explore the long artistic relationship between Paul Cézanne (French, 1839–1906) and Camille Pissarro (French, 1830– 1903).

Featuring 85 portrait, self-portrait, still life, and landscape paintings and seven works on paper from public and private collections from around the world, the exhibition was loosely chronological. It began in the early 1860s, when the artists met; continues through the period from 1872 to 1882, when they worked side by side in Pontoise and Auvers at intermittent intervals; and concludes in the mutual influence evident in their works by the mid-1880s. This exhibition reunited for the first time paintings that were executed when the artists worked together side-by-side; as well as works with the same motifs made a few years apart. All of the works in the exhibition that were in private collections had rarely, if ever, been shown in public, making this an exceptional opportunity to view the results of a compelling artistic dialogue.

The exhibition traveled to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (October 20, 2005, to January 16, 2006) and the Musée d’Orsay, Paris (February 28 to May 28, 2006).

Pioneering Modern Painting demonstrates how closely the careers of Cézanne and Pissarro are intertwined—how they mutually supported, enriched, and critiqued each other over the course of their friendship. The exhibition also shows the artists’ development during a period when they were struggling to define themselves and modern art. By juxtaposing the development of two careers, the exhibition explores the multiple origins of modern painting and demonstrates that, paradoxically, each artist, through his intense collaboration with the other, developed distinct and individual expressions.

Years after their intense pictorial dialogue, Pissarro reflected on Cézanne’s works and said, “What is curious… is that you can see the kinship there between some works he did at Auvers or Pontoise, and mine. What do you expect! We were always together! What is certain, though, is that each of us kept the only thing that matters: ‘one’s sensation!’”

Pissarro was born in 1830 on the island of St. Thomas in the West Indies (now the Virgin Islands) to a Jewish family. As a young man, rather than joining the family business he moved to France to become an artist.

Cézanne, born in 1839, also went against his family wishes by moving to Paris from Provence and taking up the paintbrush. His father was the founder of a bank in Provence—a region with its own distinct culture, where French was spoken in an accent drastically different from that of Parisians.

Both Cézanne and Pissarro were outsiders to the Parisian art world when they met in 1861. They were drawn to radical politics, and their discontent with society was inextricably bound with their dissatisfaction with prevailing academic styles. In 1863, due to the numerous artworks rejected by the jury of the Salon de Paris, an annual government-sanctioned exhibition, Cézanne and Pissarro were given the option to exhibit their rejected work in the Salon des Refusés, which had been authorized by Emperor Napoléon III as a marginal forum for artists who had failed at the Salon de Paris. Their approach to art was linked to their shared anarchistic views shared by both artists: Cézanne boasted that his paintings would shock and enrage the Salon jury and Pissarro declared that the Louvre should be set on fire.

The 1860s was a period of seminal importance for the development of Cézanne’s and Pissarro’s art and careers and served as a stepping-stone in the formation of the vocabulary of modern painting. For example, each applied unprecedented, thick layers of paint on canvas that created a coarse, almost sculptural surface of pigment. This method can be seen in

Pissarro’s landscape Square at La Roche-Guyon (1866-67)

and Cézanne’s Dominique Aubert, the Artist’s Uncle (1866).

And, throughout their friendship, the artists pushed themselves, and each other, to develop new painting techniques. They experimented with the application of paint to the canvas with the palette knife and the paintbrush. Later on, continuing to experiment with their art, they developed a method of leaving a thin line of exposed canvas around forms in order to delineate the contours of the objects they depicted. This method of painting “in reserve” seen throughout the exhibition established a contrast of volumes between objects and background.

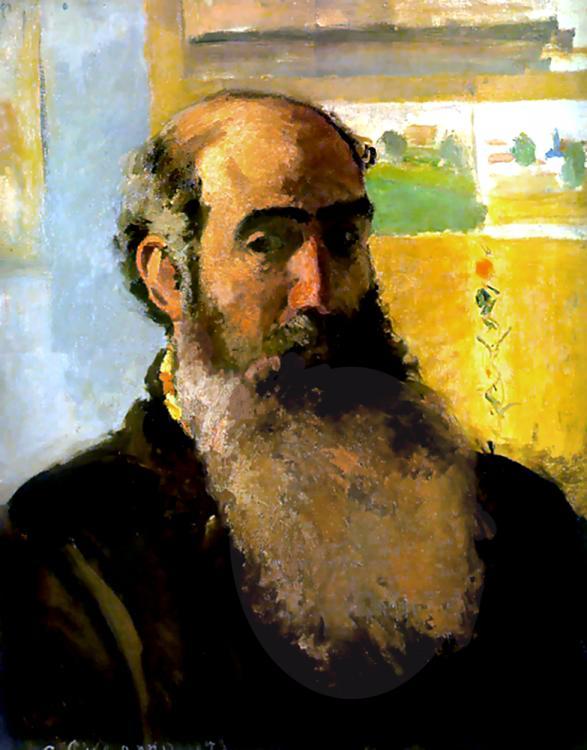

The exhibition began with a pair of self-portraits installed on the first wall. The paintings,

Cézanne’s from 1873–76

and Pissarro’s from c. 1873,

show how each artist saw himself during this early stage in their relationship. The 45-year-old Pissarro appears as a gentle nonconformist, with a long beard that gives him a biblical air, while Cézanne, still in his thirties, has shaggy hair and a defiant gaze.

Beginning in 1872, Cézanne moved to Pontoise in order to work in this area with Pissarro. According to Pissarro, Pontoise is where Cézanne “came under my influence and I his.” A pair of paintings almost indistinguishable from one another,

both titled Louveciennes (Pissarro’s is from 1871; Cézanne’s is c.1872), demonstrates how closely the artists worked together by the early 1870s and constitutes an apex in the history of Impressionism. The two works capture identical views of the village Louveciennes. Cézanne borrowed Pissarro’s canvas and created his own version of it, simplifying the composition and emphasizing individual patches of red, orange, and yellow.

The two artists painted the same motifs in Pontoise, often side by side, but also at different times, including

Cézanne’s The House of the Hanged Man, Auvers-sur-Oise (1873)

and Pissarro’s The Conversation, chemin du chou, Pontoise (1874)

both of which had been exhibited in the First Impressionist Exhibition in 1874.

The dialogue between the artists continued throughout the 1870s, taking the form of conversations, letters, and, above all, stylistic responses in paint to each other’s works that reveal the extent of their study of each other’s art. Around 1875, during the height of their collaboration, the similarities of their works speak volumes about the intensity of their exchange.

Two paintings depicting the same motifs from that year,

Cézanne’s Road at Pontoise

and Pissarro’s Rue de l’Hermitage, Pontoise,

are examples of how closely they worked together.

Also, both artists were finding artistic directions that would take them beyond Impressionism as illustrated in

Cézanne’s L’Etang des Soeurs, Osny, near Pontoise

and Pissarro’s Small Bridge, Pontoise,

both from 1875.

The artists’ continuous respect of each other is evident in two paintings of 1877, both titled

Orchard, Côte Saint-Denis, at Pontoise. Both paintings were exhibited at the Third Impressionist Exhibition and reveal moments in their careers when they looked at each other’s works to inspire, but not heavily influence, their own painting styles.

By 1881, Cézanne begins to revisit Pissarro’s earlier work and said that “if Pissarro had always painted as in 1870, he would have been strongest among all of us.”

The pairing of Cézanne’s Jalais Hill, Pontoise (1879–81)

and Pissarro’s Jalais Hill, Pontoise (1867) demonstrated how Cézanne continued to admire the solid intensity of earlier works by Pissarro while breaking down each plane into myriads of parallel brushstrokes in his own works.

In 1882, the artists executed their last pair of paintings together—

Cézanne’s Houses at Pontoise, near Valhermeil and Pissarro’s Path and Hills, Pointoise.

They continued to be aware of each other’s activities until the mid-1880s—several of Pissarro’s paintings from this time are clearly a direct response to Cézanne’s parallel, diagonal brushstrokes. They probably had their final interaction in Paris around 1885, yet each remained acutely aware of, even fascinated by, what the other was doing as they lay the foundations for subsequent developments in painting. As their relationship came to an end, Pissarro forged ahead with Neo-Impressionism, joining forces with the younger artists Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, and Cézanne returned to the south, where he soon embarked upon monumental figurative compositions such as The Bather (c. 1885), on view on the fifth floor of the Museum.

Publication

Pioneering Modern Painting: Cézanne and Pissarro 1865–1885, by Joachim Pissarro, explores the interchange and offers new insights into both the shared and the distinctive elements of the two artists’ aesthetic sensibilities.