The first monographic survey of Dosso Dossi's work included some 60 paintings carefully chosen to reflect the richness and quality of the artist's achievement. On view January 14 through March 28, 1999 at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Dosso Dossi, Court Painter in Renaissance Ferrara featured rarely lent masterpieces from collections in America and Europe — above all, the Borghese Gallery in Rome — and offered a unique opportunity to experience the full scope of Dosso's work, not seen since the dispersal of Ferrara's artistic treasures following the end of Este rule in the late 16th century.

The exhibition was organized by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Ministero per i Beni Culturali e Ambientali (Gallerie Nazionali di Ferrara, Bologna e Modena), the Comune di Ferrara/Civiche Gallerie d'Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, and The J. Paul Getty Museum.

More About the Artist

Dosso Dossi's exquisite depictions of religious subjects, allegories, and mythological scenes exemplify 16th-century court painting in its highest form. Consummate expressions of aesthetic poetry and artistic eccentricity, these paintings are also records of the refined taste and style of one of the great centers of Renaissance Italy.

In Orlando Furioso — the most widely read epic poem of the 16th century — Dosso is listed alongside Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, and Titian as one of the great figures of his age by the renowned Renaissance poet Ludovico Ariosto, who likely admired Dosso's poetic and subtle — indeed enigmatic — representations of myth and allegory. Dosso's paintings have long been appreciated as celebrations of pictorial freedom and artistic invention, characterized by a rich palette, brilliant contrasts of light and shadow, and by the enduring echoes of joyousness, wit, and sensual delight. With the devolution of the Ferrarese court into the papal states in 1598, virtually all of Dosso's oil paintings were dispersed to collections in Rome and Modena, removing them from the elaborate context for which they were created. In this exhibition, they are reunited after 400 years and their original context newly reinterpreted.

An extraordinarily accomplished painter of nature, Dosso set most of his compositions outdoors, incorporating vibrant depictions of forests, flowers, and animals into verdant and exotic landscape vistas. Although he painted exceptionally powerful altarpieces and other religious works, his most remarkable canvases are the secular scenes painted to amuse, inspire, and delight the highly refined sensibilities of his patrons at the ducal court. Combining literary allusion, humor, and fantasy with lush color, dramatic atmospheric effects, and expressive brushwork, Dosso created beguiling visions of poetry in paint.

More About the Exhibition

Dosso Dossi, Court Painter in Renaissance Ferrara included many of the artist's masterpieces. Among the highlights of the exhibition were the Metropolitan's own

The Three Ages of Man (ca. 1514-15),

the lyrically beautiful Jupiter, Mercury, and Virtue (ca. 1523-24, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna),

as well as the sophisticated Allegory with Pan (ca. 1529-32, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles).

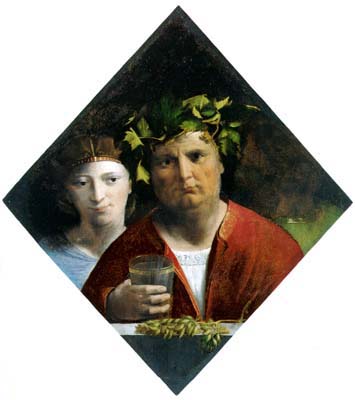

Seven rhomboid-shaped panels painted for Duke Alfonso's bedroom depict such allegories as

Anger (ca. 1515-16, Palazzo Cini, Venice),

Drunkenness (ca. 1521-22, Galleria Estense, Modena),

Love (ca. 1525-26, Estense), and Seduction (ca. 1525-28, Estense) with characteristic insight and wit.

-large.jpg)

Melissa (ca. 1515-16), a splendid work on loan from the Borghese Gallery in Rome, is thought to portray Ariosto's benevolent enchantress undoing the spell cast by the evil Alcina, by turning a beautifully rendered dog back into a knight, whose armor lies nearby. With its heroically scaled figure, luminous palette, and wonderful sensitivity to the play of light on metal, fabric, and foliage, this is one of the artist's most memorable images.

The exhibition featured several canvases —

Aeneas in the Elysian Fields (ca. 1522, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa),

The Sicilian Games (ca. 1522, Barber Institute of Fine Arts, University of Birmingham, England),

Scene from a Legend (Aeneas and Achates on the Libyan Coast) (ca. 1517-18, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.) —

commissioned for Alfonso's camerino, or private quarters within the castle. Among the most renowned commissions of the Renaissance, the camerino was undertaken by Alfonso to rival the great art collections of other rulers, including his sister Isabella d'Este in Mantua. Originally meant to include works by the most celebrated artists from various artistic centers, it eventually became a showcase for Venetian art by Bellini, Titian, and Dosso.

After Alfonso's death in 1534, Dosso continued to work for his son, Duke Ercole II, albeit on a diminished scale and often in collaboration with his brother and chief assistant, Battista Dossi. A section of the exhibition was devoted to these collaborative works as well as those by Battista alone.

Born near Mantua about 1486, Dosso's early style was formed in Venice, under the spell of Giorgione's poetic vision. Like Giorgione, Dosso was among the first painters to improvise on canvas. Rather than following careful preparatory drawings, he composed and recomposed as he painted — a remarkably free process that is revealed in new x-ray and infrared photographs, taken as part of a major technical study of Dosso's oeuvre conducted for this exhibition. Dosso worked alongside Titian on important commissions in Ferrara, is mentioned in Raphael's correspondence, and studied Michelangelo's work in Rome. While his work shows his appreciation of their prodigious talents, their influence is always reinterpreted to create something that is uniquely Dosso's.

By the time Dosso Dossi arrived in Ferrara in 1513, the city already had a long history of court painting in which artistic imagination and individuality were highly prized. Almost immediately, Dosso became court painter to Duke Alfonso I, frescoing in his beloved villas, known as "delizie", and designing theater sets, tapestries, ephemeral works. In a period that is noted for both the cultural refinement and political audacity of its leaders, Duke Alfonso I was one of the most colorful figures. He took an enormous interest in the artistic endeavors of his court and often participated in them — creating his own ceramics, musical instruments, and artillery. That so legendary a patron, whose family's collection included works by Mantegna, Bellini, and Titian, as well as Northern European artists such as Rogier van der Weyden, would choose Dosso Dossi as his principal painter is an indication of the esteem in which the artist's vision and style were held.

Publication

The exhibition was accompanied by an illustrated catalogue published by The Metropolitan Museum of Art. The 328-page catalogue features 103 color plates and 105 black-and-white illustrations and includes essays on the artist's life and work, as well as technical observations on each painting derived from the recently conducted research. Also included in the publication are a chronology and bibliography.

A major component of the catalogue reports on the extensive technical research into Dosso's painting technique and materials that was conducted over the past three years and has resulted in a critical reassessment of much of the artist's oeuvre. Some 90 works attributed to Dosso have been carefully studied and have revealed the artist's unique working method, in which the compositions of his paintings were often thought out directly on the canvas. In a large number of the artist's works, major compositional changes can be seen in the successive layers of paint. X-ray photographs of both Melissa and Allegory with Pan reveal that figures were added and subtracted, drastically altering the final look and content of the paintings from their initial conceptions. This research — presented here for the first time — has also assisted scholars in resolving issues of authorship for several problematic works previously attributed to Dosso.

Prior to the Metropolitan's presentation, the exhibition was on view in Ferrara at the Palazzo dei Diamanti. It was on view at The J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles from April 27 through July 11, 1999.