The Gilded Age: Treasures from the Smithsonian American Art Museum, on view at the Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts at Stanford University from March 28 to June 17, 2001, captured the brilliance of turn-of-the-century society and a new current of sophistication in America. The exhibition includes 60 major artworks by the most important artists of the day, including Childe Hassam, Winslow Homer, and John Singer Sargent. "Great ambition characterized this period in America," said Elizabeth Broun, director of the Smithsonian American Art Museum. "Artists and patrons rose to new heights, as the 1876 Centennial engendered a strong sense of national pride and eagerness to match Europe's aristocracies."

The Gilded Age: Treasures from the Smithsonian American Art Museum was one of eight exhibitions in Treasures to Go, touring the nation through 2002.

Mark Twain wrote a popular novel in 1873 in which he described the period, The Gilded Age, as America's "golden road to fortune." He contrasted the shallow materialism of the turn-of-the-century with the golden age of Greece. The Gilded Age, more than any other time in America, pointed to European ideals of aristocracy and patronage with a heretofore unknown collaboration between wealthy American patrons and artists.

A heightened sophistication permeates the portraits in the exhibition. Society portraitist John Singer Sargent posed

Elizabeth Winthrop Chanler (1893),

whose family was heir to John Jacob Astor's fortune, in his London studio, flanked by old master paintings.

Cecilia Beaux portrayed her brother-in-law Henry Sturgis Drinker, a hard-driving corporate railroad lawyer, as relaxed and casual in

Man with the Cat (1898), resplendent in a white suit and pink shirt.

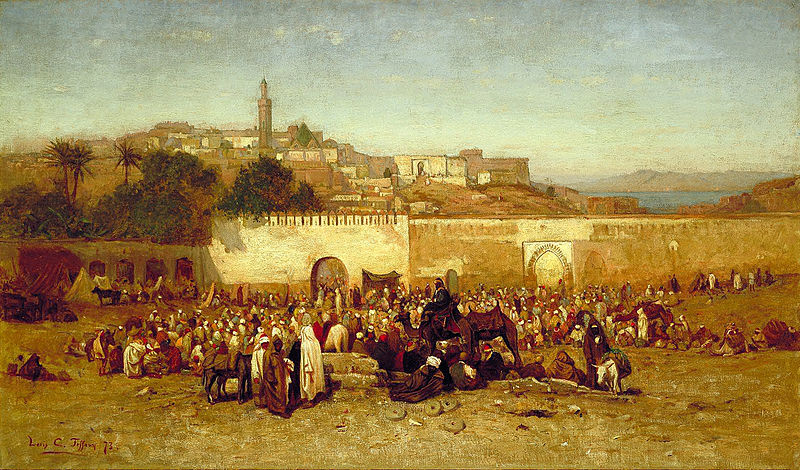

This was also an international age, when artists and their patrons traveled widely to visit exotic cultures.

Louis Comfort Tiffany's Market Day Outside the Walls of Tangiers, Morocco (1873)

signals this interest and foreshadows the artist's later development of opulent interiors. Near Eastern subjects were popular for their lush color and languorous sensuality, as in

Frederick Arthur Bridgman's Oriental Interior (1884) and

H. Siddons Mowbray's intimate Idle Hours (1895).

Vast fortunes amassed during the Industrial Revolution led to a wave of elegant townhouses, and these were settings for fine collections and decorations.

Apollo with Cupids (1880-82), a decorative panel by Augustus Saint-Gaudens and John La Farge, once adorned the dining room of Cornelius Vanderbilt's Fifth Avenue mansion in New York City. The work is lavishly embellished with African mahogany, hammered bronze, colored marbles, mother-of-pearl, and ivory.

American sculptors mastered the art of bronze casting during this period, learning to use its sleek surfaces and rich patinas to great decorative effect. Twelve bronzes were in the exhibition, ranging from Daniel Chester French's patriotic and restrained Concord Minute Man of 1774 (modeled in 1889) to Adolph Weinman's moody Descending Night (modeled about 1915) and exuberant Rising Sun (1914-15). The most famous sculptor of the period was Augustus Saint-Gaudens, represented in this exhibition by several works, including an early model for the Diana (1889) that once graced the top of Madison Square Garden in New York.

Four rare paintings by the visionary artist Albert Pinkham Ryder were in the exhibition, each a story of betrayal and redemption based on literary sources.

The Flying Dutchman (about 1887)

portrays the legendary "phantom ship" with the glowing color, dramatic composition, and complex layered painting technique that made Ryder a favorite among collectors. The same complex technique causes his paintings to be unusually fragile, so the museum rarely lends his works. Special humidity-controlled packing and shipping technology allows these works to be shared throughout America.

Winslow Homer, like Ryder, probed beneath the glitter of the Gilded Age to explore undercurrents of anxiety.

High Cliff, Coast of Maine (1894) is among the greatest of Homer's late seascapes, filling the canvas with waves pounding on a rocky shore. The opposing forces of nature resonated in a society struggling with economic instability, labor unrest, and controversial new theories of Darwin and Freud.

The intimate world of women and children at home, seen in

An Interlude (1907) by Sergeant Kendall, offered a comforting refuge. Yet danger could invade even the sanctuary of the home, as portrayed by

J. Bond Francisco in The Sick Child (1893),

in which a mother keeps watch as her son hovers between life and death.

Artists and their patrons shared an ambition to present American civilization as having grown past its earlier provincialism to full maturity, equal to Europe's much-admired culture. Evocations of music abound, as in

Childe Hassam's woman at a piano called Improvisation (1899)

and Thomas Dewing's allegory of Music (about 1895), where a prevailing gold palette evokes a musical tonality.

Spiritual themes—countering fears that Americans were overly materialistic—appear in Abbott Thayer's four paintings included in the exhibition, including the ever-popular

Angel (about 1889).

Overall, the ambitions of individual artists and patrons, and of the nation at large, combined to make the period of the 1870s through the 1910s an era of enormous achievement in the visual arts.

An illustrated gift book The Gilded Age: Treasures from the Smithsonian American Art Museum, authored by Elizabeth Prelinger and co-published by Watson-Guptill Publications, a division of BPI Communications, accompanied the exhibition. The book includes fifty color illustrations with short discussions of each artwork.