From October 8, 2010, to January 9, 2011, the Albertina presented the first comprehensive exhibition dedicated to Michelangelo in more than twenty years. The presentation of more than a hundred of the artist’s most precious drawings provided fascinating insights into the creative work of this great genius. It retraced the development of his depiction of the human body, from the delicate figures drawn in beautiful lines of the early Renaissance to a new, monumental body ideal that has kept its validity down to the present day.

The drawings presented in this exhibition were from the Albertina’s own holdings as well as from thirty of the most renowned international museums and art collections, including the Uffizi and the Casa Buonarroti in Florence, the Louvre in Paris, the Metropolitan Museum in New York, the Teylers Museum in Haarlem, the Royal Collection in Windsor Castle, and the British Museum in London.

(Click on links for more information)

Michelangelo Buonarroti was a sculptor, architect, painter, and graphic artist. The exhibition in the Albertina focused on his drawing oeuvre. As a medium for developing new ideas and conveying artistic thoughts, the drawing was the basis of all his creative work. In addition, it achieved a new status as an autonomous artwork under the great Florentine artist. In the seventy-five years of his artistic career, Michelangelo (1475-1564) created an extremely complex oeuvre, influencing not only his entire era but also subsequent generations of artists.

On the basis of Michelangelo’s most important commissions and groups of drawings, the exhibition in the Albertina presented his work in its proper chronological sequence, not least in order to illustrate the development of the master’s drawing oeuvre. The selection on display spanned the entire period from his earliest extant drawing (a copy after Giotto) and the drafts for The Battle of Cascina to the preliminary drawings for the famous frescoes in the Sistine Chapel and the subtle presentation sheets for Michelangelo’s friend Tommaso de’ Cavalieri, to the late Crucifixion depictions by the almost eighty-year-old artist. Furthermore, it featured projects the master realized while in the service of several popes and princes: the Tomb of Pope Julius II, the Medici Chapel, The Last Judgment, as well as the design for the dome of Saint Peter’s Basilica. Complementing the selection are works by pupils and fellow artists to whom art-historical scholarship has often attributed drawings by Michelangelo in the past, although their style clearly differs from that of the great master. Finally, the exhibition included a number of paintings based on drafts by Michelangelo.

The declared objective of the exhibition was to reposition Michelangelo as a graphic artist. Following losses through the vagaries of history as well as by the artist’s own destruction of several of his works, only some 600 drawings remain today. The ongoing discussion concerning their authenticity and chronology served Dr. Achim Gnann, the curator of the exhibition, as a point of departure in conceiving this presentation over a period of about three years.

Michelangelo and His Era

Michelangelo lived in an era of armed conflict and profound change. The invention of printing from movable type, the understanding of central perspective, the discovery of America, the first circumnavigation of the world, and the adoption of a heliocentric worldview expanded the spatial and intellectual horizons of the early modern age. The autonomy of the individual and his capacity for critical thought and creative power were formulated as central convictions of the Renaissance. This new self-image permitted artists like Michelangelo to adopt a self-confident posture in their dealings with mighty princes. It was in this intellectual climate that Michelangelo became a sculptor, painter, draftsman, and architect. Michelangelo experienced—and influenced—the development from the early Italian Renaissance and Mannerism to the beginning of the Baroque period. He witnessed the power struggle between the Medici and the Vatican, served under nine popes, and also perceived the influence of the checkered history in his own work. On the basis of Michelangelo’s central projects, the exhibition in the Albertina retraces the development of his creative career in the context of the cultural and political events of the Renaissance.

The Human Body in the Drawings of Michelangelo

The thematic link that connects the artworks on display is the human body. In his exemplary oeuvre Michelangelo created a vocabulary of movements and postures that would serve as a reference to many subsequent generations of artists. Michelangelo replaced the delicate figural lines of artists such as Botticelli, Filippino Lippi, and Domenico Ghirlandaio with a new monumental ideal of the human body. He created figures of great dramatic expression, lending them monumentality and heroic power. At the same time, his works are characterized by deep inner feeling and emotional tension. The human body as aesthetic leitmotiv, which is the focus of interest in Michelangelo’s work, characterized the Renaissance period. The new conviction that the description of the body reflects the innermost emotions of the soul emerged in this era, and Michelangelo rendered the concept in a particularly impressive manner.

The Drawing—A Medium for Developing New Ideas and an Autonomous Artwork

While studying Michelangelo’s richly varied and extremely detailed drawings, we also follow the artist’s train of thought. The genre of drawing, which forms such an essential part of his oeuvre, is undoubtedly the most pure and unbroken expression of an artistic idea. In Michelangelo’s works, it is no longer merely a preliminary study; it achieves a new status as an autonomous artwork. Contemporaries of Michelangelo collected his drawings, which the artist considered primarily as material he needed for his work, and guarded them like precious gems.

Early Drawings

Michelangelo showed a keen interest in drawing even as a boy. When his father sent the thirteen year old for an apprenticeship under the important Florentine painter Domenico Ghirlandaio, the latter was immediately astounded by his pupil’s exceptional talent. The artist’s early pen-and-ink drawings are unmistakably in keeping with Ghirlandaio’s technique, yet his lines are straighter, more regular, and more controlled. The position and function of each detail is clearly defined and sculpturally translatable. In the beginning, the artist liked to combine two different colors of ink, thus loosening the line-work and lending the composition a more colorful impression. It was a common practice in the workshop training of apprentices for pupils to copy the works of great artists. Michelangelo is said to have copied various sheets by older masters in a faithful manner, before coloring, smearing, and smoking them to make them appear old. Among the earliest drawings of his youth are the three famous copies based on frescoes by Giotto

and Masaccio,

whom Michelangelo admired for their simplicity and coherent figural language. Following their example, he developed a new ideal of depicting the human figure, characterized by dignified greatness, heroic grandeur, and monumentality.

The Battle of Cascina

After the fall of the Medici and the establishment of the Republic of Florence, the government commissioned a decorative program for its seat in the Palazzo della Signoria (Palazzo Vecchio). In a kind of artistic contest, the young Michelangelo in 1504 faced the experienced artist Leonardo da Vinci, who in 1503 had started to paint

The Battle of Anghiari (1440) against the Duchy of Milan,

while Michelangelo depicted the dramatic events of July 28, 1364, in

The Battle of Cascina. Michelangelo chose the moment between the surprise attack and the reaction of the soldiers, who rushed to arms. While Leonardo staged the dynamic clash of riders and soldiers in all its brutality and violence, Michelangelo structured his composition on three spatial levels and conceived the event as an “allegory of vigilance.” His contemporaries were immediately fascinated by his draft because of the expressive, richly varied postures and complex rotational movements of the bodies. The three-dimensional definition of the figures and the effort to make them space-encompassing was yet another achievement that had a lasting effect on subsequent generations of artists.

The Sistine Chapel

With the ascendance to the papacy of Julius II (1503), Michelangelo had secured his most important patron. In 1505 he summoned Michelangelo to Rome to build his papal tomb. When the construction of the new Saint Peter’s became an increasingly important priority for the pope, however, he commissioned the artist to paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. Disappointed at having to break off the tomb project on which he was already working, Michelangelo, who saw himself primarily as a sculptor, was initially reluctant to accept the new commission.

Study

He independently developed his complex program of scenes from the story of the Creation and the lives of the patriarchs Moses and Noah accompanied by the biblical prophets and the ancestors of Christ combined with figures from heathen mythology.

The Tomb of Julius II

Monumental tomb study

In 1505 Julius II gave Michelangelo his first commission: to create a monumental personal tomb in the old Saint Peter’s. It was to surpass every existing tomb in size, magnificence, and the richness of its sculptural decoration, with more than 40 figures to glorify the pontiff’s political and cultural achievements. Initially conceived as a grand project, it was to be recorded in Michelangelo’s artistic biography as the “tragedy of his life.” The execution of the original plan was prevented by other papal commissions.

Wall tomb study

Following the death of Julius II in February 1513, his heirs altered the design, rejecting the free-standing, walk-in mausoleum in favor of a still-impressive but significantly smaller wall tomb. While the first draft provided for a program of classical sculpture, Christian motifs were predominant in the later designs. No use was made of the famous sculptures of the Slaves in Paris and Florence in later project phases.

The Medici Chapel

In 1519 Michelangelo received his largest commission to date: to design the Medici Chapel in San Lorenzo in Florence along with its sculptural program. Cardinal Giulio de’ Medici and Pope Leo X commissioned this project for constructing tombs for the most important members of the Medici family. Michelangelo based his architectural structure on Brunelleschi’s Old Sacristy to which the Medici Chapel was added as a counterpart. He set new standards, however, with his completely new formal language. The three-dimensional architectural elements combine with the sculpture in harmonious unity. The artist studied individual parts of the figures in several careful drawings in order to arrive finally at the uniquely sensual gestures and introverted spiritual expressiveness. Michelangelo’s final move to Rome in 1534 as well as the death of the Medici pope at the time, Clemens VII, prevented him from ever completing this huge Gesamtkunstwerk.

Leda and the Swan

During Michelangelo’s stay in Ferrara in 1529, Duke Alfonso I d’Este presented his famous art collection to him and expressed his wish to receive a painting by the master. Upon this request, Michelangelo created a tempera painting of Leda and the Swan within a year. According to the Greek myth, Zeus admired Leda, the wife of King Tyndareus of Sparta, and seduced her in the guise of a swan. The duke sent an envoy to Florence who made disparaging remarks about the painting, whereupon Michelangelo presented it as a gift to his pupil Antonio Mini. Later the painting of Leda made its way to Fontainebleau and was burned there a hundred years later because of its lascivious subject matter. The painted copies in London’s National Gallery and by Peter Paul Rubens are not based on the painting but on Michelangelo’s cartoon, which Mini took with him to France along with the painting in order to sell them both.

Presentation Drawings for Tommaso de’ Cavalieri

At the age of 57, Michelangelo met the 17-year-old Roman nobleman Tommaso de’ Cavalieri. He was immediately smitten by the youth’s beauty, distinguished appearance, and intellect, and their meeting marked the beginning of a lifelong friendship. Michelangelo sent Tommaso sonnets, letters, and drawings in which he expressed his love for him. He promoted the young man’s artistic interest and taught him how to draw. The drawings that Michelangelo presented to Tommaso as gifts—

The Punishment of Tityus,

The Rape of Ganymede,

The Fall of Phaeton,

and A Children’s Bacchanal

—are executed in an extremely subtle, detailed, and accomplished manner, depicting classical, mythological subjects. In addition the master created drawings of “divine heads” (teste divine) for him, including that of Cleopatra, presented here.

The Last Judgment

With Pope Clement VII another member of the Medici dynasty entered the Vatican. His papacy was marked by the sack of Rome (1527) when the Medici were exiled from Florence, military defeat, and the advance of the Protestants. Nevertheless he was a generous patron of the arts, and Michelangelo’s fresco The Last Judgment for the altar wall of the Sistine Chapel is the most important work commissioned during his papacy.

As he had done earlier with his ceiling frescoes, Michelangelo designed a dramatic depiction of human fate, interpreting the Last Judgment as a monumental apocalyptic vision of the thought of redemption and the terror of damnation. Here again, Michelangelo combines the biblical narrative with scenes from ancient mythology. The connection with the Inferno from Dante’s Divine Comedy can be seen at the bottom of the fresco in the figure of Charon, the ferryman carrying the dead to the underworld. In the dynamic postures and foreshortening of the figures reaching in all directions as well as in their sculptural quality and moving, powerful expressiveness we experience the master’s visionary imagination in all its creative diversity. During this period of crisis in the church and the resulting efforts to reform it, Michelangelo made the acquaintance of the Roman poetess Vittoria Colonna, under whose influence he entered a phase of deep spirituality and religiosity in his artistry. In this spirit and as a reflection on his own mortality, Michelangelo created his late Crucifixion and Pietà scenes.

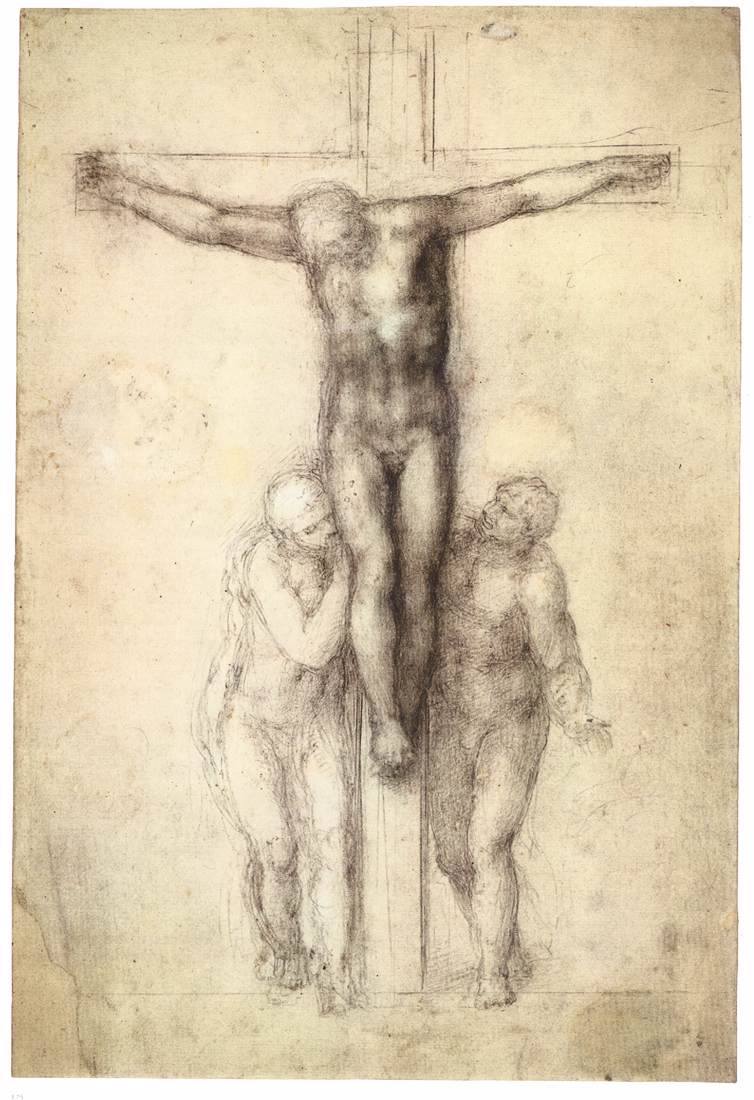

Late Crucifixion Drawings

The three poignant depictions of the Crucifixion of Christ belong to a series of stylistically related drawings on the subject. They are frequently attributed to the artist’s last creative period, although the exact date of their creation cannot be established with certainty. In these drawings Michelangelo focuses on the essential, omits decorative details, and reduces the figures to simple, block-like forms. Standing beneath the Cross are Saint John and the Mother of God. They are left entirely to their own devices in an empty space that dramatically reveals the hopelessness of their situation. They are either plainly venting their grief and desperation or recoiling in reaction to the icy-cold sensation that Christ’s death on the Cross has evoked within them. These drawings bear testimony to the deeply religious beliefs of Michelangelo, whose thoughts revolved around Christ’s death and salvation toward the end of his life.

More images here:

Artist´s biography

Michelangelo is born on March 6, 1475, in Caprese near Arezzo, where his father is mayor. His mother dies when he is six. He spends his childhood with a foster mother in Settignano. As a boy he accompanies her husband, a mason, to the nearby quarries.Michelangelo attends a Latin school in Florence. His father apprentices him at the age of twelve to the painter Domenico Ghirlandaio.At this time the great city-state of Florence is a cultural stronghold of Humanism but at the same time a city embattled on all sides.From 1488 to 1492 Michelangelo lives in Florence at the court of Lorenzo il Magnifico, where he studies the Medici collection of antiquities. In the mortuary of the Ospedale di Santo Spirito he studies the anatomy of the human body. In order to demonstrate his talent, he successfully presents artificially aged drawings as originals. Michelangelo’s outstanding talent for copying the frescoes in Santa Maria del Carmine attracts the envy of his colleagues. Pietro Torrigiani breaks his nose, thus permanently disfiguring him. The Dominican monk Savonarola causes political unrest with his fanatical preaching against ostentation and immorality. Botticelli is among the converts, burning his pagan works and ceasing his activity as an artist. The Medici are driven from Florence, which becomes a republic in 1494. Michelangelo flees to Venice and Bologna.

In 1495 Michelangelo returns to Florence and sells one of his sculptures as a work of antiquity, having artificially aged the surface. He thus demonstrates that his art is equal to the sculpture of antiquity.Michelangelo’s father, having lost his position and faced with the lack of success of his other sons, must rely to the end of his life on Michelangelo’s support.

In Rome three years later, Michelangelo executes his celebrated Pietà for the tomb of the French Cardinal Lagraulas in Santa Petronilla (today in St. Peter’s, Rome). The emphasis on suffering found in Gothic lamentation scenes is replaced by lyric idealism. In 1501 the Florentine cathedral workshop asks the now-famous sculptor to complete work on a block of marble that had suffered under the hands of previous sculptors for several decades. For a sum three times higher than that originally offered, Michelangelo creates the David. More than four meters high, the sculpture is put on display outside the Palazzo Vecchio in 1504. In an exemplary manner, it unites the principles of the High Renaissance: knowledge of antique sculpture, the study of nature, and a balance between realism and idealism. In the same year Michelangelo accepts the challenge to compete with Leonardo da Vinci in painting the most famous battle scenes in art history on opposite walls of the Palazzo Vecchio. Michelangelo’s contemporaries enthusiastically receive his cartoon and preparatory drawings for a fresco that is never to be executed. His drafts feature figures exploring the space around them in every direction, depicted in a wide variety of postures with complicated foreshortening. Michelangelo’s new ideal of the human body is to influence generations of artists from Rubens to Delacroix.

Under Pope Julius II (1503-1513) Rome replaces Florence as the center of Renaissance art. The artloving pontiff becomes Michelangelo’s most important patron. Their fruitful collaboration, however, is complicated by the difficult relationship between the two quick-tempered men. Many of the artist’s works remain unfinished and go down in art history as “perfect torsos.” The first commission that Michelangelo receives from Julius II is for a monumental tomb in St. Peter’s. It turns into a tragedy for the artist and takes more than 40 years to complete. Disagreements with the pope lead Michelangelo to return secretly to Florence. In 1506 Michelangelo witnesses the most spectacular archeological find of his day: the Laocoön group of sculpture. Its dramatic energy influences the characteristic terribilità of his figures. Julius II hires the most important artists of the day to work at his court: Bramante designs the new St. Peter’s, Raphael paints frescoes in the private apartments of the pope (Stanze di Raffaello), and Michelangelo completes his ceiling frescoes in the Sistine Chapel over four years (1508-1512), a legacy that is his greatest work of painting. After the violent end of the Florentine Republic (1512), the Medici return to power following an absence of more than 20 years. One year later a member of the Medici family is elevated to the papacy as Leo X (1513-1521).

In 1519 Michelangelo undertakes the sculptural and architectural design of the family tomb in the Medici Chapel and the adjoining Biblioteca Laurenziana at San Lorenzo in Florence. This large Gesamtkunstwerk also remains unfinished when Michelangelo moves to Rome in 1533. With the election in 1523 of the Medici pope Clemens VII (1523-1534) Rome hopes for the kind of cultural heyday it experienced under Julius II. Not least because of the pope’s hesitant policies and lack of willingness to reform, Rome is sacked in 1527 by German mercenaries in the hire of Emperor Charles V. The pope is driven from Rome. Florence is once again proclaimed to be a republic. Michelangelo changes sides again and accepts responsibility for the fortifications of the Florentine Republic. In Rome, Michelangelo meets the 17-year-old, Humanistically schooled Tommaso de’ Cavalieri. The older artist creates intimate sonnets and sensitive mythological drawings dedicated to the young nobleman. Their content suggests a deep platonic friendship between the two men. In 1533 Pope Clemens VII commissions Michelangelo to paint The Last Judgment on the altar wall of the Sistine Chapel; eight years later the artist completes the fresco under Pope Paul III (1534-1549).

Michelangelo’s free interpretation and the nudity of the figures are considered scandalous. Some twenty years later Michelangelo’s pupil Daniele da Volterra is given the unpleasant task of painting loincloths on several of the figures. This results in the nickname “Il braghettone” (“the breeches maker”). In this period Michelangelo establishes first contacts with the Roman poetess Vittoria Colonna. Under her influence he becomes acquainted with the spiritual ambitions of the Roman Catholic Counter-Reformation. The heartfelt Pietà and Crucifixion scenes of his later years attest to his newly internalized religious feelings.

In 1534/35 the new Farnese pope, Paul III, releases Michelangelo from the time-consuming contract for the Tomb of Julius II in order to force the artist to work for him. He puts Michelangelo in charge of all artistic matters at the Vatican. Over the next few years Michelangelo works primarily as an architect. As project manager for construction of the new St. Peter’s, he designs a spectacularly monumental central-plan building, but it is never executed. Giorgio Vasari publishes the first edition of his biographies of artists (1553), which includes that of Michelangelo, the first that he has written about a living artist. Vasari founds the first academy of drawing in Florence in 1563. Thus he establishes drawing not only as an indispensable discipline for every budding artist: as the purest version of the idea, it is considered the mother of all artistic genres. Michelangelo’s marble group for a Pietà (Cathedral Museum, Florence), which the 75-year-old artist creates for his own tomb, remains, like an alternative version, the Rondanini Pietà, unfinished. Michelangelo dies on February 18, 1564, only a few days before his eighty-ninth birthday. His nephew Leonardo Buonarroti secretly brings the body to Florence, where Michelangelo is celebrated in a solemn funeral procession as the greatest genius of his time.