“Variations on America: Masterworks from American Art Forum Collections” celebrated the vision and passion of private collectors who are formally affiliated with the Smithsonian American Art Museum. The exhibition presented 72 major artworks, several of which are rarely on public display, from 26 distinguished private collections by some of America’s most talented and cherished artists, including John Singer Sargent, Edward Hopper and Georgia O’Keeffe.

The exhibition was on view from April 13 through July 2 2007. “Variations on America” featured a wide range of paintings, watercolors, pastels, decorative arts and sculptures from the mid-19th century through the 20th century, selected by Chief Curator Eleanor Harvey and Deputy Chief Curator George Gurney.

The exhibition was presented in loose chronological groupings, beginning with two early portraits of children, each touched with sadness.

Henry Inman’s “Mistippee” (about 1833)

shows a young Creek boy, whose tribe was part of the “Trail of Tears” forced migration to the west.

Sarah Miriam Peale’s “Mary Leopold Griffith (1838–1841)” (1841)

is a posthumous portrait of a child felled by illness.

James McNeill Whistler’s “Harmony in Grey: Chelsea in Ice” (1864),

painted soon after his mother came to live with him in London, is one of the artist’s first great experiments with abstraction, prefiguring developments in his art almost a decade later. Broad swaths of grey and tan and white evoke ice floes on the Thames River, with the distant city nearly obscured in smoke and haze.

The exhibition included more than 10 seascapes and landscapes from the 1870s and 1880s, among them major artworks by Sanford Robinson Gifford, Martin Johnson Heade, Winslow Homer, John Singer Sargent and Francis A. Silva, which suggest the variety of expression American artists found in nature.

Frederic Edwin Church’s “View from Olana in the Snow” (1871–1872)

is a magesterial view across the open landscape and river near the artist’s new home near Hudson, N.Y.

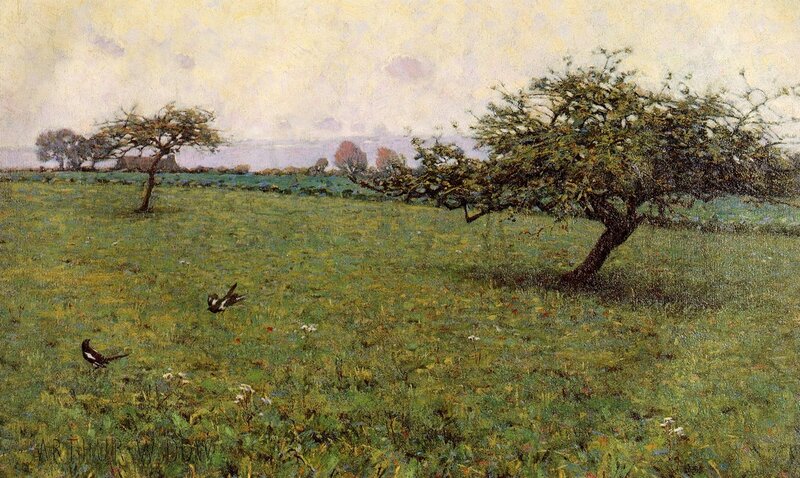

Arthur Wesley Dow’s “A Field, Kerlaouen” (1885),

often considered his finest work, creates an unusually intense mood through the handling of trees, an open field and an overcast sky.

Narrative paintings were included, such as

Eastman Johnson’s “Cardplaying at Fryeburg, Maine” (about 1865),

one of his best works celebrating the annual ritual of making maple sugar—a return to rural pleasures at a time of Civil War.

William McGregor Paxton, in “The Breakfast” (1911),

shows how a new marriage can be fraught with tension, even before the morning coffee cups have been cleared.

Some featured objects had not been on public view in many decades. The exhibition is a rare opportunity to see Louis Comfort Tiffany’s acclaimed three-panel stained glass “Dining Room Screen with Autumnal Fruits” (about 1900). When Tiffany exhibited the screen at the 1900 Paris Exposition Internationale, he was awarded the grand prize, beating his rivals René Lalique and Émile Gallé.

A delightful contrast was Reginald Marsh’s hilarious three-panel “Golf Course Scene” (1922), lampooning the foibles and fashions of golfers.

Three bronze sculptures capture the ambivalent and elegiac concern for Native American cultures early in the 20th century, after wars and broken treaties had forever transformed traditional tribal cultures. Adolph Weinman’s “Chief Blackbird—Ogalalla Sioux” (modeled 1903), Cyrus Dallin’s “Appeal to the Great Spirit” (modeled 1912) and James Earle Fraser’s “End of the Trail” (1918) summarize these complex emotions. These were joined by significant works depicting southwestern subjects by artists associated with the Taos School, including Ernest L. Blumenschein, Bert Geer Phillips and E. Martin Hennings.

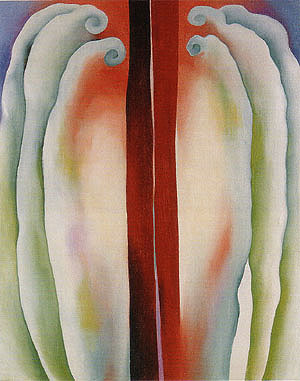

Nearby, four major oil paintings by Georgia O’Keeffe revealed the range of her accomplishment, from the delicate blushed tones and vitalistic forms in

“Red Lines” (1923)

that recalled her earliest abstractions to the richly contrasting

“Birch and Pine Trees—Pink” (1925)

painted near Lake George to the monumental

“Black Cross with Red Sky” (1929)

that reveals the profound impact of her first trip to New Mexico

to the explosive

“Black Place No. IV” (1944)

with its surging land forms and burning colors.

One of the largest groupings was work by the Ashcan School artists who turned from academic studio painting to city streets and public parks and beaches for subjects. Two masterful and brisk pastels by Everett Shinn—

“Madison Square, Dewey Arch” (1899)

and “Washington Arch, After the Rain” (1902)—

contrast the daily routines of the average city dweller with the grand public monuments then appearing around New York City.

George Bellows’ “Noon” (1908)

presents industry and construction in the city as an heroic enterprise;

while

William Glackens’ “The Purple Dress” (1908–1910)

and Guy Pène du Bois’ “Intellect and Intuition” (1918)

focus on the “new woman” emerging in the age of suffrage marches and liberated lifestyles.

Three extraordinary oils celebrate the spectacle of leisure activities carried out in the public sphere, for all to watch:

Robert Henri’s

“At Joinville” (1896)

and “Far Rockaway” (1902),

and William Glackens’ “In the Buen Retiro” (1906)

A choice selection of eight watercolors was a rare chance to see works that are seldom exhibited because of their light-sensitivity.

Winslow Homer’s

“Watching Ships, Gloucester” (1875),

with three small boys in straw hats gazing out to sea, is among his most affecting works on the subject of American innocence.

Thomas Moran’s impressive

“Hot Springs of Gardiner’s River” (1872)

records the surreal hues of Yellowstone’s sulfur springs.

Maurice Prendergast’s

“Summer Visitors” (1896)

is a tour-de-force of technique, with 21 figures navigating stepping stones among the pools of water along Nantasket Beach near Boston, all on a 19 by 15-inch sheet of paper. Superb watercolors by Thomas Anshutz, John Marin, Edward Hopper and Andrew Wyeth complete this group.

Wyeth’s two watercolors were displayed with a major tempera painting by the artist called

“The Quaker” (1975)

that commemorates his father, N.C. Wyeth, and his father’s teacher, Howard Pyle.

Two paintings by Willem de Kooning— “Torso” (late 1950s)

and “Stowaway” (1986)

—are separated by almost 30 years, but displayed remarkable similarities in color and brushwork.

Two paintings by David Hockney—

“Savings and Loan Building” (1967)

and “Savings and Loan Building” (1987)

—show the artist’s canny reprocessing of minimalism and cubism into a witty personal vision.

Among the other modern and contemporary artworks are a large David Smith bronze sculpture and impressive canvases by Tom Wesselmann, Richard Estes, Alice Neel, Wayne Thiebaud and David Bates.

The exhibition concluded with a 10-foot-tall sculpture by Niki de Saint Phalle titled “La Lune” (1987), in which a goddess’ head appears within a mirrored crescent moon, atop a lobster and turtles encrusted with glass mosaic.

Publication

The catalog, co-published by the Smithsonian American Art Museum and D Giles Ltd London, features color reproductions of each artwork with extended entries by the museum’s curators and a foreword by Broun.

Another image from the exhibition:

Reading“Le Figaro”

by Mary Cassatt, ca. 1877-1878, oil, 39 3/4 x 32. Private collection.