Wednesday, January 30, 2013

Manet and the Execution of Maximilian

Manet and the Execution of Maximilian united for the first time in the United States a series of compositions created between 1867 and 1869 by Edouard Manet that depict the execution of Emperor Maximilian of Mexico. The exhibition—featuring the series of three large paintings, an oil sketch, and one lithograph—examined the evolution from one painting to the next, which was fueled by a steady stream of written and graphic accounts of the event. Also included in the exhibition were selected works by photographers and other artists who documented the event or whose pictures were likely sources for what Manet produced.

Additionally, a small group of canvases by Manet is included to add context to the Maximilian works. This exhibition was on view from November 5, 2006, to January 29, 2007.

Napoleon III, seeking to assert France’s economic and political power over Mexico, appointed Maximilian, a member of the Hapsburg family of Austria, emperor of that country in 1864. Three years later, Maximilian was abandoned by the French government when Napoleon III withdrew troops assigned to protect him, and was subsequently tried and executed for treason by the resurgent Mexican army. News of the execution reached Paris on July 1, 1867, and Manet, opposed to Napoleon III’s policies, immediately began the first painting in the series.

History

In 1861, Benito Juárez became President of Mexico and, due to the collapse of the nation’s economy, declared a moratorium on payments of foreign debt. Britain, France, and Spain decided to coerce him into payment, but France was the only country that took the initiative seriously. Napoleon III of France disliked Juárez’s liberal beliefs and felt that Mexico could fall prey to United States aggression. Napoleon III sought to assert France’s economic and political power over Mexico and sent Archduke Maximilian of Austria, a member of the Hapsburg family, to assume leadership of the alliance.

In 1863, a French expeditionary force expelled Juárez from Mexico City, allowing Maximilian to assume his position as emperor there one year later. Three years after Maximilian settled in Mexico City, Juárez’s guerilla forces gained strength, and French control of Mexico declined. Napoleon III, convinced he had made a mistake, withdrew French troops from Mexico, abandoning Maximilian and his few supporters. Juárez’s army easily defeated Maximilian at Querétaro, north of Mexico City, in May 1867. Maximilian and two of his generals—Miguel Miramón, who had been president of the Mexican Republic before Juárez, and Tomás Mejía, an indigenous soldier from the hills outside Querétaro—were tried on June 13, and the following day the death sentence was announced for all three defendants. As the news spread, some Mexican supporters wanted to aid Maximilian’s escape, but he refused. Others pleaded with Juárez to pardon him, but he declined, fearing that Maximilian would set up a government in exile. Many Europeans, ranging from Queen Victoria of England to the author Victor Hugo, sent telegrams to Juárez urging him to spare Maximilian’s life. On June 19, 1867, Maximilian and his two generals were executed by the firing squad of Juárez’s army on Cerro de las Campanas (Hill of the Bells), near Querétaro.

The Execution of Maximilian Series

Manet, who was opposed to Napoleon III’s policies, responded to the ongoing accounts of Maximilian’s death as they were published in French journals. These accounts—which came from eyewitnesses, signed and anonymous letters, and various foreign publications—presented many inconsistencies about the time of day and site of the execution and the number of victims and soldiers involved. This exhibition included a selection of photographs, some taken by François Aubert, Maximilian’s official photographer, and engravings that Manet might have seen published in the French newspapers.

The series included three large paintings that currently reside, in order of creation, in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; in The National Gallery, London; and in the Städtische Kunsthalle, Mannheim. The other two works are a small painting that served as a study for the Mannheim painting, now in the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen, and a lithograph, in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, which was made in the same period as the Copenhagen painting.

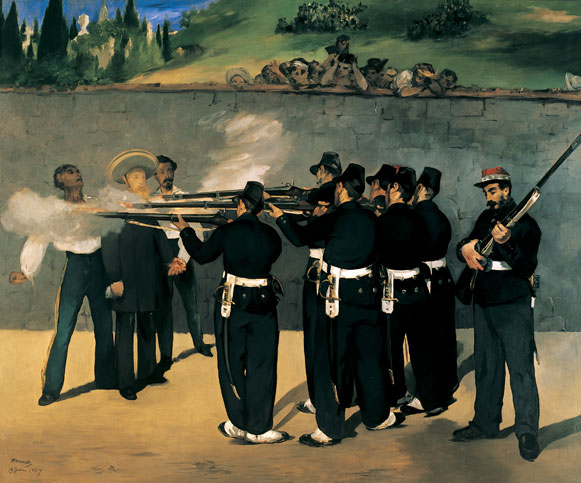

The first painting in the series, begun in 1867, is a large canvas with nearly life-size figures. The painterly brushstrokes and the atmospheric quality may reflect the ambiguity of early reports of Maximilian’s death, as well as revealing the influence of

Francisco de Goya’s The Third of May, 1808, which Manet had seen in Madrid two years earlier. Manet changed elements in the painting as news filtered into France. For instance, the flared trousers and outlines of sombreros indicate that Manet had originally painted the soldiers in Mexican guerilla uniforms rather than the uniforms of Juárez’s regular army.

By autumn 1867, as more details about Maximilian’s death were published, Manet set aside the first painting and began a second, more refined canvas (1867–68). This second painting formed the basis on which the remaining works were composed. He reworked the background, altered the distance between the victims and the firing squad, and changed the uniforms of the soldiers so that they resembled French army uniforms. This painting exists in fragments, having been damaged while in storage in Manet’s studio. In the 1890s, Edgar Degas sought out the surviving fragments and brought them together again. The National Gallery acquired the fragments in 1918, and in 1992 reassembled them onto one canvas to afford at least a partial sense of what the composition had originally looked like.

The small oil sketch (1868-69)

and the lithograph (1868-69) were made in preparation for the final painting (1868–69), which is the largest and most definitive work. New reports and photographs pertaining to the execution continued to appear in French newspapers, influencing Manet’s final work.

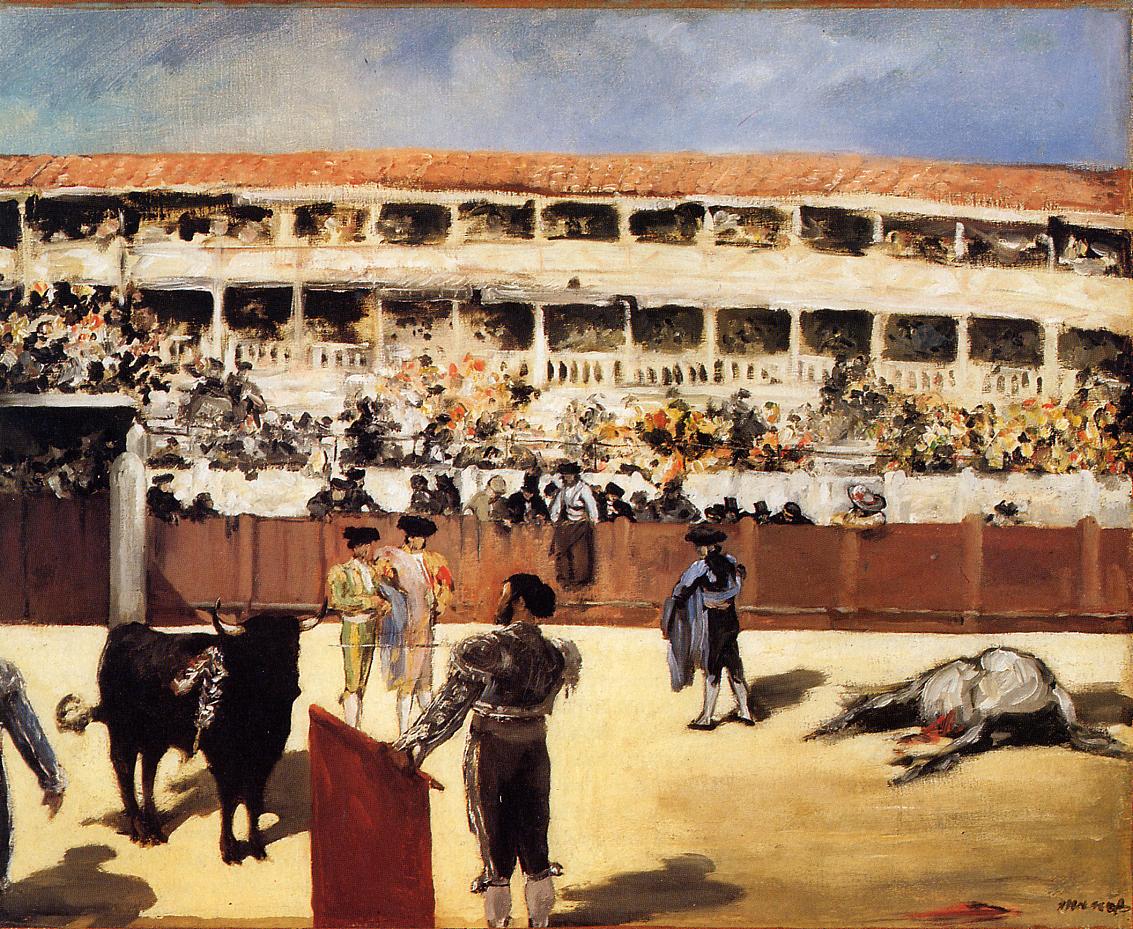

To this composition, Manet added a background landscape with spectators that was borrowed from an earlier painting from 1865–66,

titled Bullfight, which in turn referenced

Francisco de Goya’s La Tauromaquia (Bullfight) prints from 1816. This painting and a print from Goya’s series were also included in this exhibition.

In addition to Bullfight, the exhibition included others works by Manet to add historic and aesthetic context to the series.

The Dead Toreador was a part of a composition called Incident in a Bullfight, which Manet began in 1862 after the French defeated Juárez’s forces. Manet excised this portion of the painting, reworked it and exhibited it in 1867 as The Dead Man. This title change coincided with Maximilian’s surrender to Juárez’s forces.

Also included was

The Funeral (c. 1867), inspired by the funeral of his friend, the poet Charles Baudelaire, which Manet created while he was working on the Maximilian series. This painting would become the source for the cemetery and landscape in the background of the final painting of Maximilian’s execution. The Maximilian series also influenced a later work on paper titled The Barricade (1871), which depicts a crowd of Communards in the streets of Paris being fired upon by French soldiers, the figures of which are derived from a tracing of the Maximilian lithograph.

PUBLICATION:

In the book that accompanied this exhibition, John Elderfield analyzes and documents the creation of the works and discusses their art-historical importance in the context of modern art. The book also includes a bibliography and newspaper excerpts from Parisian newspapers that circulated in Paris at the time of Maximilian’s execution. The book was published by The Museum of Modern Art 200 pages; 112 illustrations.