University of Arizona Museum of Art

May 27, 2010 – October 31, 2010

Fritz Lang’s 1927 film, Metropolis, is justifiably famous for its iconic imagery and advancements in film technique. Although the plot itself is considered the weakest part of the movie, the themes presented in the film addressed important concepts being debated in the years between the two world wars: labor issues, class division, industrialization, mechanization, architecture, and the nature of modernity.

This exhibition explores works from both the UAMA Permanent Collection and the fine arts collection of the Center for Creative Photography (CCP) to see how artists addressed these themes, either in design or in meaning. The exhibition is divided into sections focusing on specific aspects of the film. The viewer will discover that the indecisive approach in the film’s plot to many of the issues of the day reflects the ambivalence and confusion of society as a whole to the unfolding future.

From a review of the show: (images added)

William Wolfson pays homage to heroic

"Asphalt Workers"

and "Rock Drillers" in two wonderful lithographs, from 1928 and 1932. The men in these black-and-white prints are proud of what they do—work that requires skill and brawn. They lean over their tasks in deep concentration, their backs forming beautiful curves. The rock-drillers are even posed like conquerors, laboring high on an elegant cliff sculpted into Art Deco lines.

But many of the pieces betray the era's anxiety about mass production and the isolation of the modern, anonymous city.

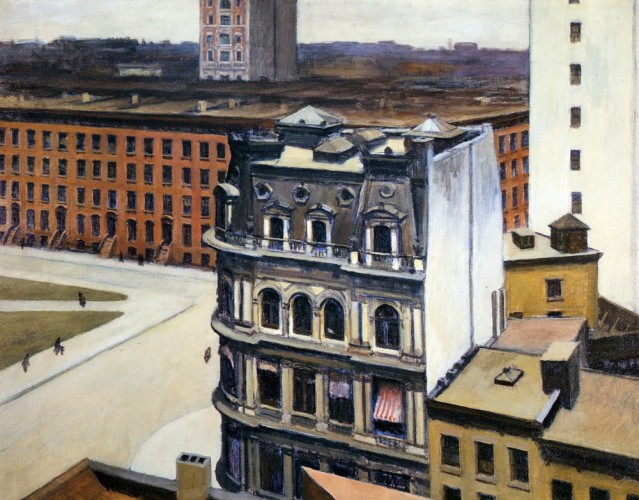

Edward Hopper's 1927 painting "The City"

is a bleak vision of New York from on high. A block of red rowhouses forms a barrier at one side; there's also a high-rise mansard-style apartment building. Only a few people walk in the public square below; most of them are alone. Beyond, on the horizon, is an endless cascade of buildings under a chilly winter sky.

Richard Aberle Florsheim's "Tests the Cities" is another view of an intimidating city, made several decades later, in 1951. In his black-and-white lithograph, one man stands front and center, his back toward the viewer. Before him is a scary city, with two lines of forbidding skyscrapers sloping downward to the vanishing point in the distant horizon. Inside the shadows cast by these monoliths are small, blurry figures. They could be the poor, the homeless and the ignored—or they could be soldiers defending the status quo, armed and ready to shoot…

A dramatic 1923 woodcut by noted German artist Käthe Kollwitz encapsulates the agony of workers who've become cogs in the machine. Ironically titled

"Die Freiwilligen"

— German for "the volunteers"—it's full of curves and bold shapes, printed in vivid black and white. Its workers are bound together in a row, their heads thrown back, their mouths open. They're screaming as they march forward, relentlessly, toward the end of the workday, toward their own death: The laborer at the head of the line has already turned into a skeleton. Even so, he keeps on keeping on, his bony hand held aloft.

The Swiss-American Herman Volz pictured what happened too often to laborers who tried to better their lot. In 1936, in the depths of the Great Depression, he made

"Lockout,"

a black-and-white lithograph of workers shut out of their jobs. A crowd of them gaze at the factory behind the wall, where a giant machine rises up, operating without them. Sketched in simple, rounded forms, the workers have lost their jobs because they tried to organize against The Man...

One whole wall of photos and prints in the show celebrated the beauty of the modern big city, and the sheer miracle of the Big Apple in particular.

Berenice Abbott's 1933 photo "Exchange Place, New York"

is an exuberant view of one of the city's "slot canyons," a narrow band of light and air between granite monoliths.

Several of the artists celebrate the architecture of industry.

Charles Sheeler's "Architectural Cadences"

is a lovely silkscreen in grays and blues from 1934. Its lively assemblage of rectangles and triangles adds up to a factory building, seen as a grand contributor to the nation's well-being.

Fernand Léger's "Les Constructeurs," 1950.

The French painter Fernand Léger celebrated not only architecture but labor in his 1950 "Les Constructeurs" (the construction workers). Two heroic workers are on the I-beams of a skyscraper under construction in this beautiful painting, a gouache on paper. Léger abandons the black and white of his pessimistic colleagues in the show, and moves into optimistic color. The beams, lightly colored in yellow, turquoise and pink, bounded in deep gray, dart across the paper in diagonals and verticals.

The two workers are perched high above the earth. A far cry from Lang's robot slave and underground workers, they're masters of their craft, masters of the city below. One sits astride the metal, while the other, lightly tethered to the beam by one hand, leans fearlessly out into the air.