Adelson Galleries in New York City January 19 through March 3, 2007

Museo Correr, Venice, 24 March/22 July 2007

Sargent and Venice, a spectacular artist’s view of the fabled city, was shown in an exhibition that opened in January 2007 at Adelson Galleries in New York city.

John Singer Sargent (1856-1925), one of a few truly international artists of the 19th century, had a love affair with Venice: he traveled there numerous times over 40 years. Adelson Galleries in New York, noted for its expertise in American art and the work of John Singer Sargent in particular, has organized an exceptional loan exhibition, Sargent and Venice, comprising of approximately 60 oils and watercolors painted by the artist from the 1880s until 1913.

The exhibition was on view at the gallery from January 19 through March 3, 2007 and then traveled to the Museo Correr in Venice —marking the artist’s first-ever solo exhibition in that city—from March 24 through July 22, 2007.

A majority of the paintings shown are on loan from private collections and have rarely been on public view; several institutions, including the Brooklyn Museum, Philadelphia Museum of Art, The National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., the Royal Academy of Arts in London, and the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza in Madrid, have loaned important works as well.

Inspired by the idea of retracing Sargent’s routes down the Venetian waterways, Warren Adelson, president of Adelson Galleries and the sponsor of the Sargent catalogue raisonné, saw this approach as a means to gather together the Venice pictures that appear throughout several volumes of John Singer Sargent: The Complete Paintings (Yale University Press).

It was the first such exhibition in New York (Adelson Galleries) and, remarkably, the venue at the Museo Correr in St. Mark's Square in Venice was the first exhibition of Sargent ever held in that magical place.

John Singer Sargent was born in Florence to American parents and lived most of his adult life in England. Widely recognized as the preeminent portrait painter of his generation, he felt equally at home in Europe and the United States where he painted many of the most notable social and political figures of his day.

Detail, Café on the Riva degli Schiavoni, Venice, ca. 1880-82'

After “Turner and Venice”, Sargent and Venice was another show which charted a great artist’s response to the city and its lagoon. Venice was, in fact, the place best loved by John Singer Sargent (1856-1925), the most important of American ‘Impressionists’, who was born in Florence and lived for most of his life in Europe.Café on the Riva degli Schiavoni, Venice, ca. 1880-82'

Housed within the neoclassical rooms on the first floor of the Museo Correr, the exhibition – curated by Warren Adelson, Elizabeth Oustinoff and Giandomenico Romanelli– was the fruit of collaboration between the Musei Civici Veneziani and Adelson Galleries of New York; it included approximately sixty works (paintings and watercolours) dating from 1880-1913. There were loans not only from the Brooklyn Museum, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, The National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., the Royal Academy of Arts in London and the Thyssen-Bornemisza in Madrid, but also from numerous private collections. Thus, the public had the opportunity to see masterpieces that are rarely if ever placed on public display.An accompanying book (published in Italian by Electa) contains essays by scholars including Warren Adelson, Elaine Kilmurray, Elizabeth Oustinoff, Richard Ormond, Rosella Mamoli Zorzi and Giandomenico Romanelli.

Like J.W.Turner and other great nineteenth-century artists, Sargent was fascinated by Venice.

The man himself had grown up in cultured cosmopolitan circles in Italy, France, Spain, Switzerland and Germany. In Paris he had studied under Carolus-Duran and then enrolled at the École des Beaux-Arts before embarking on a career as a portrait-painter.

A friend of Monet’s, he would in the second half of the 1870s undertake a number of study trips, experimenting ever more extensively with peinture en plein air.

The exhibition layout was completed by an unusual and surprising section dedicated to such contemporary Venetian painters as Milesi, Tito, Selvatico and Nono. A leading figure in a number of Venice Biennales, Sargent undoubtedly had an influence on these men; but at times he himself may have been influenced by their work.

From a NY Times review of the Venice show (images added) :

Sargent was distantly related to the Curtises, an Anglo-American family that had taken up residence at Palazzo Barbaro on the Grand Canal. Both he and Henry James, a friend since the two men had met in Paris in 1884, stayed there on several occasions.

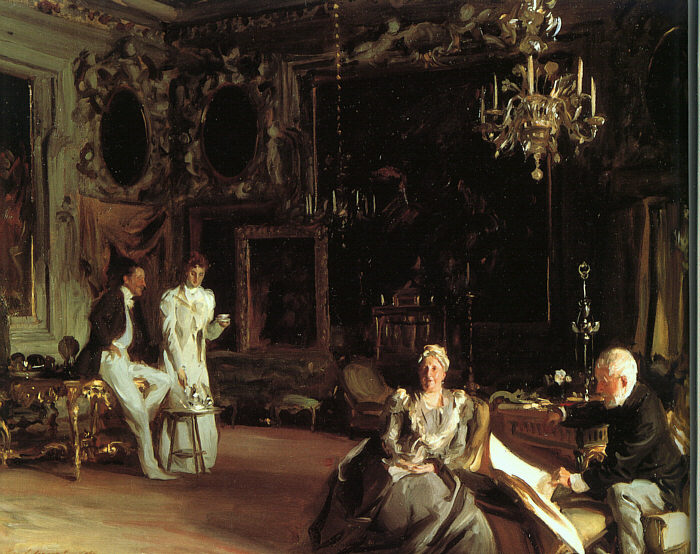

As a mark of his appreciation for the Curtises' hospitality during his visit in 1898, Sargent made an informal portrait in oils of the Curtis parents, Daniel and Ariana, their son Ralph and his young wife taking tea in the grand ballroom of the palazzo. The painting, which later acquired the title

'An Interior in Venice',

was to become one of the artist's most famous and oft-reproduced images.

When Sargent presented the picture to Ariana Curtis, she refused it, finding the likeness of herself unflattering and the raffish pose of her son Ralph, hand-on-hip, casually draping himself on a gilded table, "indecorous." Her vanity and prudery were to become the family's loss and the Royal Academy's gain. The artist subsequently gave it to that institution as his diploma picture on being received as a full member, and the Academy has been its owner ever since.

Four years later, in another rare Venetian oil, Sargent infiltrated his upper-class friend Jane de Glehn, in the garb of a proletarian local woman, into his

"Venetian Wineshop,"

a sympathetic rendering of the relaxed informality of a typical lower-class hostelry, almost a low-life pendant to the high-life drawing-room scene of "An Interior in Venice." In 1904 Sargent was to do a bravura watercolor of Jane de Glehn, stylishly dressed, elegantly posed and very much the lady, at ease in a gondola gliding along the Grand Canal...

Roger Fry, the critic and member of the Bloomsbury group in London, accused the artist of reacting to Venice "for all the world like an ordinary tourist" - a verdict few who see the pictures today will share. Certainly contemporary buyers and collectors did not concur. In the two-day-long auction at Christie's of the contents of the artist's studio after his death, the Venice pictures were the subject of frenzied bidding. One watercolor alone reached the then-staggering sum of £4,830.

More spectacular, not to be missed, images

Related book:

This gorgeously illustrated book presents nearly seventy of Sargent’s oil and watercolor paintings of Venice, many of them famous but others only rarely seen. The book also contains fascinating new photographs of actual sites depicted in Sargent’s paintings.

Sargent’s early works in Venice were created in 1880-1882, and he undertook a second, larger body of work in the city during visits from 1900 to 1913. His responses to Venice—its local figures, its buildings and waterways, its extraordinary light—reflect his changing interests over time as well as his lifelong ability to extend his own reach as a creative artist. The book considers various aspects of Sargent’s work and milieu in a series of informative essays by international scholars. They discuss the evolution of Sargent’s style, the topography of his work in Venice, his connections with Henry James and other Americans in Venice, Italian artists in Venice in the nineteenth century, and American artists in Venice in the nineteenth century.

He made his first visit to Venice in 1870, returning more than ten times over the next 40 years and taking this city as the subject of his art more frequently than any other: in effect, his particular love of Venice would, from the 1890s to 1913, be reflected in the 150 or so oils and watercolours. Approximately sixty of these works were shown in the Museo Correr exhibition. The first Venetian show to be entirely dedicated to the artist, this exhibition took the form of a gondola ride down the Grand Canal. Sargent often painted from within a gondola, rendering the unusual views afforded by this low vantage point.

Palaces, churches, campi and canals are all enlivened by the play of light on water and architectural details. However, alongside views of famous monuments such as the Rialto Bridge, the Doge’s Palace and the Church of the Salute, there are also evocations of daily life in the Venice of the time: interiors of workshops, crowded streets, women at work, busy cafés and osterie, etc. And whether interiors or external scenes, each of these works reveals the dominant features of Sargent’s art: exploration of light effects, freedom and precision of line, perfect mastery of form.

Eijk

van Otterloo was born in the Netherlands and Rose-Marie in Belgium.

They met and married in the United States, where they developed deep

ties with New England. The couple enjoys living with their collection,

but they are also dedicated to sharing it with others, generously

lending to institutions around the globe. The Van Otterloos have said,

"With Golden, we are delighted to have this opportunity to

share the entire collection with the American public. Within these

works of art lie a world of beauty, meaning and even humor. We hope

that visitors to the exhibition receive as much pleasure, inspiration

and delight from them as we do."

Eijk

van Otterloo was born in the Netherlands and Rose-Marie in Belgium.

They met and married in the United States, where they developed deep

ties with New England. The couple enjoys living with their collection,

but they are also dedicated to sharing it with others, generously

lending to institutions around the globe. The Van Otterloos have said,

"With Golden, we are delighted to have this opportunity to

share the entire collection with the American public. Within these

works of art lie a world of beauty, meaning and even humor. We hope

that visitors to the exhibition receive as much pleasure, inspiration

and delight from them as we do." Lured

by religious freedom and a better economic climate, many artists fled

northward from cities such as Antwerp, Brussels and Bruges to escape

persecution and the war with Spain in the late 1500s and early 1600s.

They introduced sophisticated new painting styles and together with

Dutch artists created a climate of artistic excellence in the Dutch

Republic.

Lured

by religious freedom and a better economic climate, many artists fled

northward from cities such as Antwerp, Brussels and Bruges to escape

persecution and the war with Spain in the late 1500s and early 1600s.

They introduced sophisticated new painting styles and together with

Dutch artists created a climate of artistic excellence in the Dutch

Republic. Dutch

cities swelled with the influx of immigrants from the south taking

refuge in religiously tolerant, albeit strongly Protestant, urban

environments. Protestant churches in the Netherlands were largely

devoid of religious imagery. Instead, artists painted images of

biblical figures and contemporary religious structures such as Jan van

der Heyden's View of the Westerkerk, Amsterdam for display in people's homes as expressions of their piety and affluence.

Dutch

cities swelled with the influx of immigrants from the south taking

refuge in religiously tolerant, albeit strongly Protestant, urban

environments. Protestant churches in the Netherlands were largely

devoid of religious imagery. Instead, artists painted images of

biblical figures and contemporary religious structures such as Jan van

der Heyden's View of the Westerkerk, Amsterdam for display in people's homes as expressions of their piety and affluence. Successful

merchants, powerful politicians, influential scholars and other

prominent individuals often commissioned portraits of themselves, their

spouses, and sometimes their children. Rembrandt's portrait of Aeltje

Uylenburgh, the unquestionable jewel of the Van Otterloo collection, is

one of the finest portraits by Rembrandt in private hands. Although the

artist painted it when he was only twenty-six, Rembrandt sensitively

rendered the effects of age and tenderly captured his subject's soft

cheeks, bright eyes, and crisp linen cap.

Successful

merchants, powerful politicians, influential scholars and other

prominent individuals often commissioned portraits of themselves, their

spouses, and sometimes their children. Rembrandt's portrait of Aeltje

Uylenburgh, the unquestionable jewel of the Van Otterloo collection, is

one of the finest portraits by Rembrandt in private hands. Although the

artist painted it when he was only twenty-six, Rembrandt sensitively

rendered the effects of age and tenderly captured his subject's soft

cheeks, bright eyes, and crisp linen cap. The

daily lives of the rich and poor became a new subject for painting

during the Dutch Golden Age. These sometimes humorous genre scenes also

contain allegorical symbolism. The importance of frugality and modesty,

and the fleeting nature of life, were especially popular themes in a

society grappling with how to express its new-found prosperity while

maintaining a pious and humble lives. In this scene by Nicolaes Maes, a

woman deftly picks the pockets of a sleeping man while coyly inviting

the viewer's silence. A beautiful and perhaps cautionary still life of

glasses, jars, pipes and tobacco alludes to the sources for the man's

drowsy vulnerability. Maes studied with Rembrandt and is regarded as

one of his most important pupils.

The

daily lives of the rich and poor became a new subject for painting

during the Dutch Golden Age. These sometimes humorous genre scenes also

contain allegorical symbolism. The importance of frugality and modesty,

and the fleeting nature of life, were especially popular themes in a

society grappling with how to express its new-found prosperity while

maintaining a pious and humble lives. In this scene by Nicolaes Maes, a

woman deftly picks the pockets of a sleeping man while coyly inviting

the viewer's silence. A beautiful and perhaps cautionary still life of

glasses, jars, pipes and tobacco alludes to the sources for the man's

drowsy vulnerability. Maes studied with Rembrandt and is regarded as

one of his most important pupils. Intrigued

by new translations of ancient Greek myths, many Dutch artists

incorporated classical imagery in their work. In this monumental canvas

by Aelbert Cuyp, Orpheus plays the violin for an enchanted menagerie of

animals from Europe and around the globe. Cuyp's ambitious paintings

not only highlight his skills as a landscape and animal painter, but

also the era's lively exchange of artistic, literary and scientific

ideas. Cuyp, who never left Europe and would not have seen many of

these animals firsthand, drew upon prints and

Intrigued

by new translations of ancient Greek myths, many Dutch artists

incorporated classical imagery in their work. In this monumental canvas

by Aelbert Cuyp, Orpheus plays the violin for an enchanted menagerie of

animals from Europe and around the globe. Cuyp's ambitious paintings

not only highlight his skills as a landscape and animal painter, but

also the era's lively exchange of artistic, literary and scientific

ideas. Cuyp, who never left Europe and would not have seen many of

these animals firsthand, drew upon prints and  stuffed

specimens in aristocratic "cabinets of curiosities" to depict them.

Allegorical imagery was not limited to paintings in 17th-century

Dutch households. The owner of this stunning four-door cupboard could

display it and avoid the criticism of ostentation because the cupboard

served as a daily reminder of his religious obligations-a veritable

"sermon in wood."

stuffed

specimens in aristocratic "cabinets of curiosities" to depict them.

Allegorical imagery was not limited to paintings in 17th-century

Dutch households. The owner of this stunning four-door cupboard could

display it and avoid the criticism of ostentation because the cupboard

served as a daily reminder of his religious obligations-a veritable

"sermon in wood." The

Dutch Republic dramatically expanded its influence and financial

prospects through voyages around the globe, becoming the dominant

international maritime power in the 17th-century.

Accordingly, Dutch artists were the first to paint the sea in its own

right - a reflection of the importance of water in the nation's psyche.

Maritime views are often characterized by precise depictions of ships

and atmospheric rendering of the weather. The fertile landscape was

similarly a favorite new subject. Cloud-filled skies billowing over a

narrow stretch of earth or sea emphasize the flat horizons for which the

Netherlands is known.

The

Dutch Republic dramatically expanded its influence and financial

prospects through voyages around the globe, becoming the dominant

international maritime power in the 17th-century.

Accordingly, Dutch artists were the first to paint the sea in its own

right - a reflection of the importance of water in the nation's psyche.

Maritime views are often characterized by precise depictions of ships

and atmospheric rendering of the weather. The fertile landscape was

similarly a favorite new subject. Cloud-filled skies billowing over a

narrow stretch of earth or sea emphasize the flat horizons for which the

Netherlands is known. The

carefully balanced compositions in Dutch still lifes are often visual

odes to prosperity and pleasure with elements of moralistic symbolism.

As the nation emerged as a powerful mercantile force, Dutch artists

filled their canvases with the staples and luxuries of the trades they

dominated - Dutch cheese, French wine, Baltic grain, South American

tobacco, and Asian porcelain and pepper.

The

carefully balanced compositions in Dutch still lifes are often visual

odes to prosperity and pleasure with elements of moralistic symbolism.

As the nation emerged as a powerful mercantile force, Dutch artists

filled their canvases with the staples and luxuries of the trades they

dominated - Dutch cheese, French wine, Baltic grain, South American

tobacco, and Asian porcelain and pepper.