The complex relationships between photography, film, painting, and drawing that were central to the art of American modernist Charles Sheeler (1883–1965) are highlighted in Charles Sheeler: Across Media. Organized by the National Gallery of Art, Washington, the exhibition features many of the artist’s greatest achievements, including striking examples from his famous 1917 series of photographs made in Doylestown, Pennsylvania; the film Manhatta, made in collaboration with Paul Strand in 1920; and two of Sheeler’s best-known paintings, the iconic images of the Ford Motor Company’s River Rouge Plant Classic Landscape (1931) and American Landscape (1930).

Organized by the National Gallery of Art, Washington, the exhibition draws on a core of masterpieces recently added to its collections, as well as loans from public and private collections. Charles Sheeler: Across Media features approximately 50 works and is accompanied by a fully-illustrated catalogue featuring a brief introductory overview of the Sheeler literature, a detailed analysis of the artist’s mediums and working methods, and a discussion of how those findings suggest new approaches to interpreting Sheeler’s work.

A celebration of both the formal clarity and beauty of Sheeler’s works, the exhibition built upon a core of masterpieces including the magnificent painting

Classic Landscape, and the masterful conté crayon drawings

Interior with Stove and Counterpoint,

as well as striking Doylestown photographs:

The Stove,

Stairwell,

and Stairway with Chair.

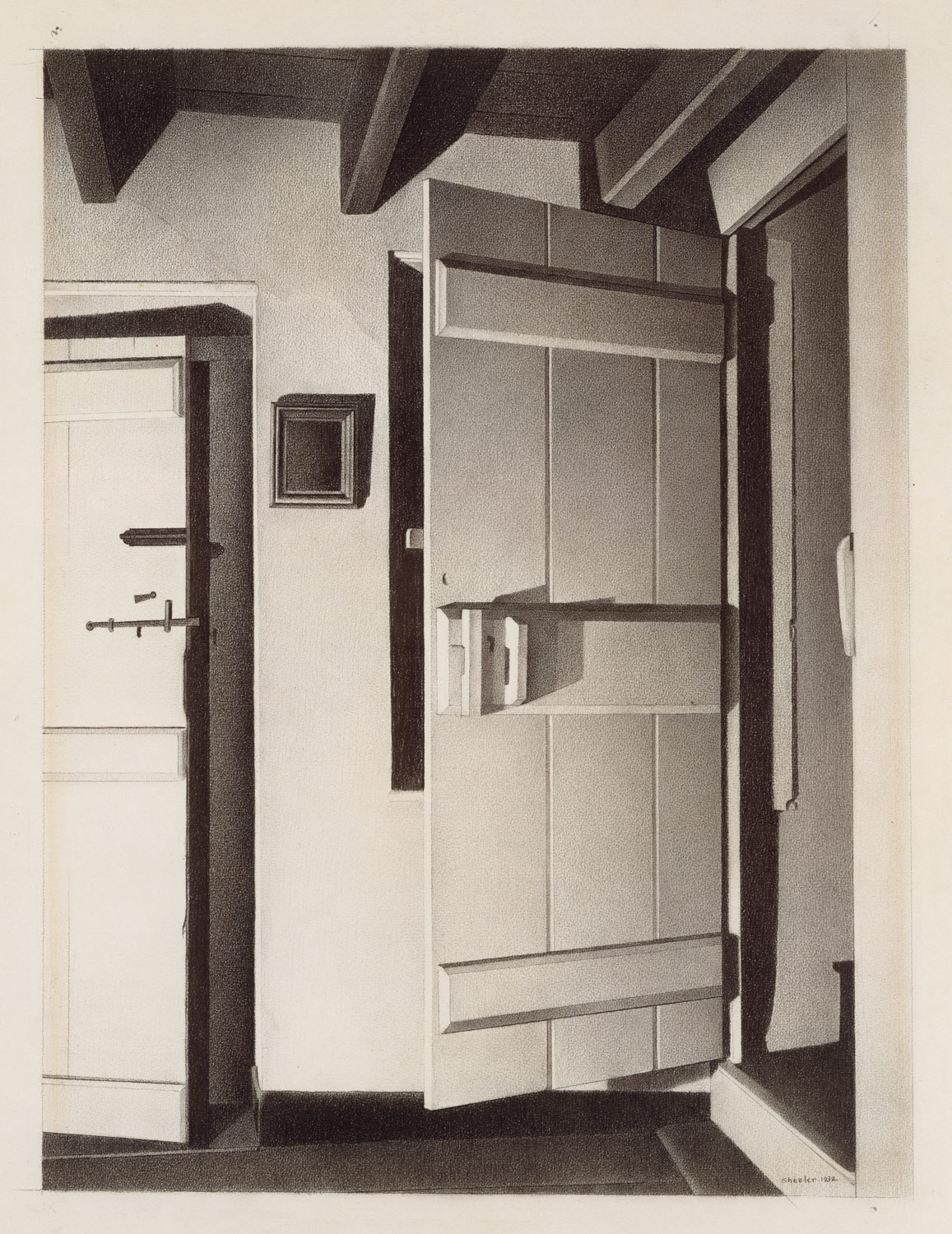

The exhibition included a small selection of Sheeler’s seminal c. 1917 photographs of the interior of an 18th-century Quaker fieldstone house in Doylestown, Pennsylvania. These highly experimental, innovative night scenes in which a familiar antiquarian subject is transformed into a modernist abstraction, as in

The Stove and

Stairway with Chair, represent Sheeler’s first major achievement as a photographer. These early photographs were immediately praised by Alfed Stieglitz and later inspired Sheeler’s drawing,

The Open Door (1932) and his painting,

The Upstairs (1938).

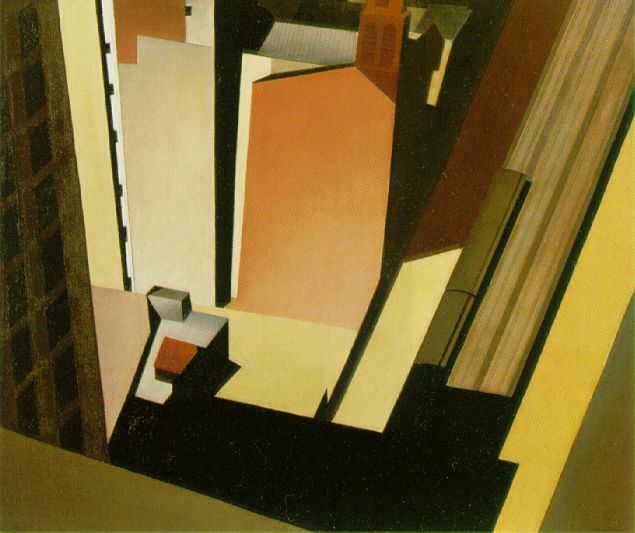

By 1920 Sheeler was collaborating with Paul Strand on Manhatta, regarded as the first avant-garde film made in the United States, and the exhibition features a vintage print of this fascinating ten-minute montage of New York City’s urban landscape with titles and poems by Walt Whitman. The footage is projected continuously in close proximity to a number of related photographs and paintings from the early 1920s, including

Church Street El (1920).

Moving from the rural to the urban to the industrial, the third component of the exhibition highlights the finest works from the series of iconic paintings and conté crayon drawings inspired by the documentary photographs that the Ford Motor Company commissioned Sheeler to produce in 1927 of the River Rouge Plant. These works, which include watercolor studies for both Classic Landscape (1928) and

American Landscape (1930) and a magnificent group of conté crayon drawings, illustrate how a mastery of various techniques enabled Sheeler to elucidate ever more subtle and intricate relationships between his different mediums. In addition, they also illustrate how Sheeler’s name became virtually synonymous with depictions of the American industrial landscape. Also featured in this section of the exhibition is a seven-by-twelve-foot photomontage mural based on Sheeler’s study, Industry (1932).

A highlight of the exhibition, which was presented alongside the works from which it is derived, was Sheeler’s enigmatic masterpiece

The Artist Looks at Nature (1943) in which Sheeler paints himself in the process of sketching the 1932 drawing, Interior with Stove, which was in turn based on the Doylestown photograph The Stove (1917). The exhibition concludes with a select group of images inspired by Sheeler’s experiments with photo-montage in the 1940s and 1950s such as Counterpoint, which are among the most complex and intriguing achievements of his entire career.

Charles Sheeler (1883–1965)

A native of Philadelphia, Sheeler was trained there from 1900 to 1902 in industrial drawing, decorative painting, and applied art at the School of industrial Art. He then attended the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fline Arts from 1903 to 1906, where he studied under William Merritt Chase and learned an impressionistic style of painting. In early 1909, on a trip to Paris, he encountered the revolutionary works of Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, and other European modernists. Recognizing the break with the past that these artists represented, he returned to the Untied States determined to pursue a new direction in his work.

Around 1910 Sheeler took up photography as a means to support his painting, and in 1913 he participated in the Armory Show in New York—the first comprehensive display of European and American modernism in the Untied States—where he greatly admired the works by the iconoclastic French artist Marcel Duchamp. By 1917 Sheeler was being recognized not only for his cubist-inspired paintings, but also for his innovative photographs. During the 1920s Sheeler found further success and recognition as a commercial photographer for Edward Steichen at Condé Nast. In the early 1930s he also designed fabrics, tableware, and glassware.

After receiving the Ford River Rouge commission in 1927, Sheeler continued to pursue industrial themes. His career was effectively ended by a debilitating stroke in 1959, but his many depictions of American industry secured his reputation during and after his lifetime.

Organization and Catalogue

Charles Sheeler; Across Media was organized by the National Gallery of Art, Washington.

The exhibition was accompanied by a catalogue titled Charles Sheeler: Across Media, written by Charles Brock, Assistant Curator of American and Paintings, National Gallery of Art. Published by the National Gallery of Art in association with UC Press. 238 pages, 50 color and 80 black-and-white illustrations.

Venues

Prior to its presentation in San Francisco, Charles Sheeler: Across Media was on

view at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. from May 7 through August 27, 2006, and at The Art Institute of Chicago from October 7, 2006 through January 7, 2007.