The art of trompe l’oeil, from its origins in classical antiquity to its impact on 20th-century artists, was presented with more than 100 works in the most comprehensive exhibition of the genre ever organized. It was at the National Gallery of Art, East Building, from October 13, 2002 through March 2, 2003. The Gallery was the sole venue for this exhibition.

Deceptions and Illusions: Five Centuries of Trompe l’Oeil Painting illustrates both the playful and intellectual nature of trompe l’oeil -- a depiction of an object, person or scene, which is so lifelike that it appears to be real. The exhibition included paintings by Europeans Samuel van Hoogstraten, Louis-Léopold Boilly, and Carel Fabritius; and Americans Charles Willson Peale, William Harnett, and John Frederick Peto, among others; as well as a few mosaics and sculptures.

"Throughout the ages, trompe l’oeil has always been one of the most popular genres while, at the same time, engaging some of the best artists in its challenges," said Earl A. Powell III, director, National Gallery of Art. "Our generous supporters and lenders have made it possible for us to organize an exhibition of art that is both accomplished and amusing."

THE EXHIBITION

Deceptions and Illusions: Five Centuries of Trompe l’Oeil Painting presented paintings from different periods within each of its sections, showing the surprising persistence of some trompe l’oeil themes over the centuries. The exhibition opened with such works as Still Life with Fruit (3rd quarter of the first century AD), a fresco found in the dining room of the House of Julius Felix, at Pompeii, and among the last works is Eaten by Duchamp (1964), a collage of various materials -- actual remains of a meal eaten by modern master Marcel Duchamp -- mounted on wood, by the Swiss artist Daniel Spoerri.

In its Prologue, Deceptions and Illusions: Five Centuries of Trompe l’Oeil Painting established the literary and visual sources of trompe l’oeil, with works of art inspired by ancient legends. One of the most famous legends comes from Hellenistic times and tells about Zeuxis, so accomplished a painter that birds flew up to his painted grapes, and his rival Parrhasios, who bested him by painting a curtain that Zeuxis tried to draw aside to see what was hidden behind it. Among the works in this section are

The Twins, Chianti Grapes (1885) by George Henry Hall

and the Portrait of Filippo Archinto (c. 1558) by Titian.

The exhibition was then divided into six sections, beginning with the Temptation for the Hand, where one of the traditional devices used by trompe l’oeil artists is introduced -- images of letters, prints, and other flat objects that appear to rest on the picture surface, as in Trompe l’Oeil (1703) by Edward Collyer and Music Stand by William Sidney Mount.

The following sections of the exhibition -- Things on the Wall; Niches, Cupboards, Cabinets; and In and Out of the Picture -- focused respectively on three-dimensional objects on a two-dimensional surface, as in

The Old Violin (1886) by William Harnett;

three-dimensional images on a three-dimensional space, as in the Cabinet of Curiosities (late 17th century) by Domenico Remps;

and blurring the boundary between real and fictitious space, as in Escaping Criticism (1874) by Pere Borrell del Caso.

and blurring the boundary between real and fictitious space, as in Escaping Criticism (1874) by Pere Borrell del Caso.

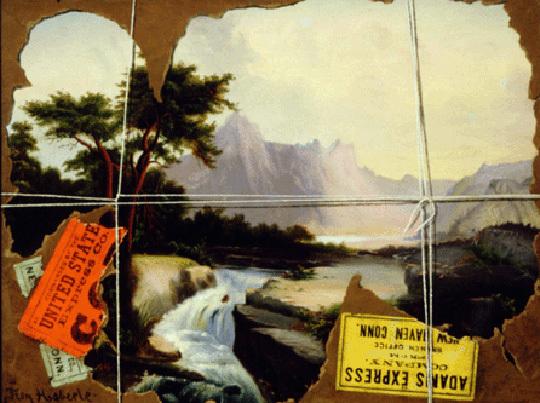

In the next section, The Painting as Object, it is not what is in the painting that was fooling the eye, but the whole painting, as an object, as in

John Haberle’s Torn in Transit (1890-1895)

and Antonio Cioci’s The Painter's Easel (c. 1775-1780), among others.

The last section, The Object as Art, investigated the legacy of the art of trompe l’oeil to 20th-century artists.

It included works such as The Two Mysteries (1966) by René Magritte,

Stretcher Frame with Cross Bars III (1968) by Roy Lichtenstein, White Brillo Boxes (1964) by Andy Warhol, and Security Guard (1990) by Duane Hanson. Although these 20th-century works of art are not trompe l’oeil, they engage with many of the genre’s intellectual traditions.

TROMPE L’OEIL: A BRIEF OVERVIEW

Trompe l’oeil, the French term for "eye-deceiver," is a modern word for an old phenomenon: a three-dimensional "perception" provoked by a flat surface, for a puzzling moment of insecurity and reflection. The early precursors of modern trompe l’oeil appeared during the Renaissance, with the discovery of mathematically correct perspective. But the fooling of the eye to the point of confusion with reality only emerged with the rise of still-life painting in the Netherlands in the l7th century.

The new genre spread throughout Europe and the United States.

Charles Willson Peale’s painting Staircase Group (1795), which was in the exhibition, is said to have fooled George Washington. Although based on l7th-century European traditions, American 19th-century trompe l’oeil painting is a genuine American genre and an important link to 20th-century art, especially to American pop art.

Though highly esteemed by collectors, from the beginning art theorists often dismissed trompe l’oeil as the lowest category of art, seeing it as a mere technical tour-de-force that did not require invention or intellectual thought. In the l7th century, trompe l’oeil masters were not only receiving praise and recognition from many quarters but also pushing the boundaries of the genre: Samuel van Hoogstraten was awarded a medal by the Holy Roman Emperor; and Cornelis Gijsbrechts had given trompe l'oeil paintings the shape of the depicted object.

In the 20th century, artists continued to probe the limits of representations, with Pablo Picasso including real objects in his cubist collages, as in Guitar (1926), also in the exhibition. By that time, modern brain research was investigating the issues of perception involved in trompe l’oeil.

EXHIBITION ORGANIZATION, CATALOGUE

Deceptions and Illusions: Five Centuries of Trompe l’Oeil Painting was organized by the National Gallery of Art, Washington. The exhibition’s guest curator was art historian Sybille Ebert-Schifferer, director at the Bibliotheca Hertziana, Max Planck Institute for Art History, Rome. The coordinating curator was Franklin Kelly, senior curator, American and British paintings, National Gallery of Art.

The exhibition was accompanied by an illustrated catalogue with essays by noted scholars in the field: Sybille Ebert-Schifferer, Wolf Singer, Paul Staiti, Alberto Veca and Arthur K. Wheelock Jr.